The Curse of Blessings

What’s the best terrible thing that’s ever happened to you? Is it some food you thought you hated, but someone made you try it and you liked it? Or did you have to go somewhere to which you desperately wanted not to go, but someone made you go and you liked it? One of my best terrible things is a musical called Merrily We Roll Along. It’s a story that moves backwards in time, from the lives in tatters of its stars at the beginning of the show to their starry-eyed beginnings at the end of the show. Merrily We Roll Along appeared on Broadway sometime in 1981 and even though it was created and produced by some of Broadway’s biggest names – Harold Prince and Stephen Sondheim – the critics hated it and it was gone in two weeks. I saw one its sixteen performances, and Merrily We Roll Along has been one of my very favorite musicals ever since.

Food, trips and Broadway musicals don’t really come close to being the worst things a person can experience. But suffering is suffering. And learning to handle life’s difficulties with grace, to even find ways to be grateful for goodnesses that still remain, these are among life’s greatest challenges.

Here’s a story called “The Curse of Blessings.” It was written by Mitchell Chefitz (from his book by the same name).

Once upon a time, there was an Officer of the Law. A newly-minted graduate of the academy, he was filled with pride, dressed in his crisp, blue uniform, adorned with brass buttons, gold epaulets, and a silver sword at his side. But the young officer, also filled with self-importance, was arrogant and cold-hearted.

One day, while walking his beat, he heard a commotion in an alleyway. Stepping into the darkness, he saw a man dressed in rags. “Come forward,” he commanded. But the man did not come forward. “I am an Officer of the Law, and I command you to come forward!” The man still did not move. Instead, he spoke, “I just don’t know what I’m going to do with you.”

“Do with me?” the Officer replied. “Do with me? You don’t do with me! I do with you! I am an Officer of the Law and I order you to come forward.”

“Ahh,” said the man in rags, “now I know what to do with you,” and as he spoke, he drew his sword. “Now I know exactly what to do,” and without another word he moved to attack.

The Officer drew his sword in defense. “Stop that!” he ordered. “Put down your sword right now or someone is going to get hurt.” But the man in rags continued moving forward. “Stop!” he said again, but to no avail, and as the man in rags thrust his sword forward, the Officer of the Law responded in kind.

In that moment, just as the young officer moved to attack, all became silent and still. Suddenly frozen in place, he could not move. But he could hear. And what he heard was the man in rags saying this: “I am leaving you – but as I do, I place upon you the Curse of Blessings. The Curse of Blessings means that every day you must offer a new blessing, one you have never spoken before. On the day you do not offer a new blessing, on that day you will die.”

And then all returned to normal. Except the man in rags was gone. The Officer of the Law lowered his sword, wondering what he had just seen and what he had just heard. “I must have imagined the whole thing,” he thought.

It was late, and the sun was setting. The Officer felt his body growing cold. Did the man in rags exist? Did he really speak those words? Was the Officer’s life leaving him?

In a panic, he blurted out a blessing: “Thank You, O God, for creating such a beautiful sunset.” At once, he felt warmth and life flow back into him, and he realized, with both shock and relief, that the curse was real.

The next day, he did not delay. Upon waking, he offered a blessing: “Praised be the Source Who has allowed me to awaken this morning.” His life felt secure the entire day. The next morning, he blessed his ability to rise from his bed; the following day, that he could tie his shoes.

Day after day, he named features that he could bless: that he could take care of his body, that he had teeth to brush, that each finger of his hands still worked, that he had toes on his feet and hair on his head. He blessed his clothes, every garment. His house, the roof and floor, his furniture, every table and chair.

One day, running out of blessings for himself, he began to bless others. He blessed his family and friends, fellow workers, and those who worked for him. He blessed the mailman and the clerks, firefighters and school teachers. He was surprised to find they appreciated his blessings. His words had power. They drew people closer. He became known as an unusual Officer of the Law, one who brought goodness wherever he’d go.

Years passed, decades. The policeman had to go further and further afield to find new sources of blessing. He blessed city councils and university buildings, scientists and their discoveries. As he traveled throughout the world, he grew in awe of its balance and beauty and he blessed that. He realized that the more he learned, the more he had to bless. His life was long, and he had the opportunity to learn in every field.

He passed the age of one hundred. Most of his friends were long gone. His time was now devoted to searching for his life’s purpose and the one source from which all blessings flow. He had long since realized that he was not the origin but merely the conduit, the channel, and even that realization was welcomed with a blessing that sustained him for yet another day.

As he approached the age of one hundred and twenty, the Officer decided that his life was long enough. Even Moses had lived no longer than that. So on his 120th birthday, he decided he’d offer no new blessing and allow his life to come to its end.

All that day he recited old blessings and reviewed all the gifts he had received throughout his life. As the sun was setting, a chill settled into his body. This time, he did not resist it. In the twilight, as his breath grew shallow, a familiar figure appeared — a man in rags.

“You!” whispered the Officer of the Law. “I have thought about you every day for a hundred years! I never meant to harm you. Please, forgive me.”

“You still don’t understand,” said the man in rags. “You don’t know who I am, do you? I am the angel who was sent one hundred years ago to harvest your soul. But when I looked at you, so arrogant and cold, so pompous and full of yourself, there was no soul there to harvest. An empty uniform, that’s all you were. So I placed upon you the Curse of Blessings, and now look what you’ve become.”

In an instant, the Officer of the Law understood all that had happened. Overwhelmed, he said, “You, my friend, have been my greatest blessing.”

The man in rags replied, “Now look what you’ve done. A new blessing!” The Officer of the Law and the man in rags looked at each other, neither knowing what to do.

Sometimes we have a million blessings and can’t see any of them. And sometimes, when blessings are in short supply — that’s when we rise to our very best, seeing the most important blessings of all, and giving thanks for our great fortune.

I want to show you a video. It’s an excerpt from Britain’s Got Talent, filmed after the tragic bombing that occurred in 2017 at an Ariana Grande concert in England’s Manchester Arena.

Two stories. The same ending: that despite colossal difficulty, we humans possess such magnificent hearts and spirits that we can come back from most anything. And when we do, we are often in possession of a greater sensitivity to all the wondrous and truly gorgeous beauty that has always existed around us.

The trick, of course, is to acquire this sensitivity without having to endure tremendous hardship.

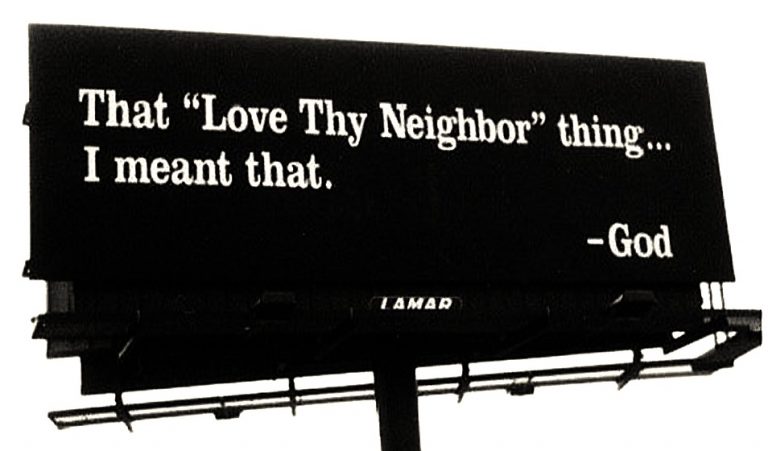

At Mount Sinai, the Torah tells us, God instructed that we should never make gods of silver or of gold (Ex 20:20). In a collection of midrashim on the book of Exodus called the Mekhilta, our rabbis interpret “gold and silver” to mean life’s best moments. “When happiness comes,” they teach, “give thanks. But when things get tough, give thanks then as well.”

The rabbis probably didn’t mean we should be happy when we’re sad, but that we should remember, even when we’re sad, that life has had its wonderful moments and, if we’ll open our hearts, we can have wonderful moments again.

Summer is almost here. Time for many of us to go play. For as long as I’ve been at Woodlands, I’ve been sending you into these lazy, frolicsome months with homework: to read a new book, think a new thought, and make a new friend. It’s just another way to remind us that life is filled with blessing, and we should keep our eyes and our hearts open every moment of every day so that we don’t miss any of them.

A horrific story of the Holocaust to share with you. Many of you will know it. Young people might not. But it describes just one small, terrible moment during which only three people died, which was pretty benign for genocide. All you have to do is multiply this moment two million times, and that gets you six million Jewish lives murdered by the Nazis during World War II.

A horrific story of the Holocaust to share with you. Many of you will know it. Young people might not. But it describes just one small, terrible moment during which only three people died, which was pretty benign for genocide. All you have to do is multiply this moment two million times, and that gets you six million Jewish lives murdered by the Nazis during World War II.

Here’s what happened. The Nazis occupied Albania in September 1943. When Adolf Eichmann called for the Final Solution to be implemented there, the Albanian response was a uniform one: “Besa.” Besa is a word that means “faith,” or “to keep the promise,” “word of honor.” It reflects the Albanian Muslim idea that when you have welcomed a guest into your home, you provide that guest every kindness and honor, withholding nothing, including, if need be, the protection of their lives. This concept extended beyond the walls of their homes to include the very borders of their nation. So when the Nazis came hunting for Jews, Albanian Muslims embarked upon an ambitious national project: to hide every one of them (including the additional 1800 souls who had sought refugee status there). Two thousand Jewish men, woman and children were protected. And except for a single family, two thousand survived.

Here’s what happened. The Nazis occupied Albania in September 1943. When Adolf Eichmann called for the Final Solution to be implemented there, the Albanian response was a uniform one: “Besa.” Besa is a word that means “faith,” or “to keep the promise,” “word of honor.” It reflects the Albanian Muslim idea that when you have welcomed a guest into your home, you provide that guest every kindness and honor, withholding nothing, including, if need be, the protection of their lives. This concept extended beyond the walls of their homes to include the very borders of their nation. So when the Nazis came hunting for Jews, Albanian Muslims embarked upon an ambitious national project: to hide every one of them (including the additional 1800 souls who had sought refugee status there). Two thousand Jewish men, woman and children were protected. And except for a single family, two thousand survived.

Of all the stories in the Torah, Noah’s is perhaps the most loved of them all. After all, who can resist the image of all those furry, adorable creatures ascending into the Ark, two by two, and living in harmonious tranquility for the duration of that epic boat ride all those thousands of years ago?

Of all the stories in the Torah, Noah’s is perhaps the most loved of them all. After all, who can resist the image of all those furry, adorable creatures ascending into the Ark, two by two, and living in harmonious tranquility for the duration of that epic boat ride all those thousands of years ago? That would be a funnier joke if so many of us weren’t as concerned as we are about the United States government. With issues like North Korea, Russia, global warming, the treatment of Muslims and the treatment of unauthorized immigrants so prominently and disappointingly in the news, it’s understandable when people express dismay to us about what awaits our nation just up ahead.

That would be a funnier joke if so many of us weren’t as concerned as we are about the United States government. With issues like North Korea, Russia, global warming, the treatment of Muslims and the treatment of unauthorized immigrants so prominently and disappointingly in the news, it’s understandable when people express dismay to us about what awaits our nation just up ahead.

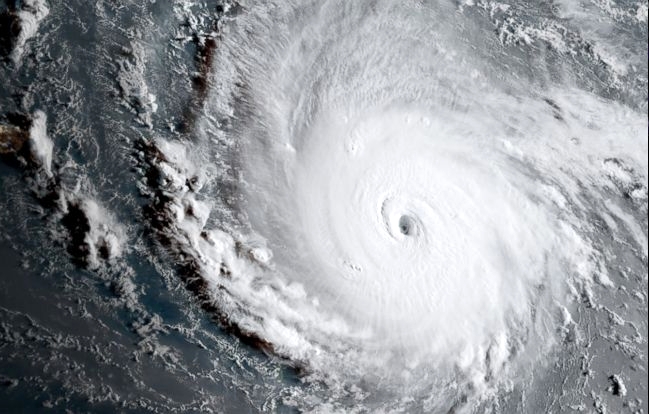

I’ve been on the phone every day this week with my brother Jimmy. He was supposed to be here tonight, sitting with you and with his family at this service, and enjoying the Kabbalat ShaBBQ afterwards. But Jimmy lives in Fort Lauderdale and, together, we’ve been watching the weather and watching Hurricane Irma. I’ve been telling him to come up here and get out of the hurricane’s path, while he’s been stocking up on supplies and telling me he needs to be there to take care of the house.

I’ve been on the phone every day this week with my brother Jimmy. He was supposed to be here tonight, sitting with you and with his family at this service, and enjoying the Kabbalat ShaBBQ afterwards. But Jimmy lives in Fort Lauderdale and, together, we’ve been watching the weather and watching Hurricane Irma. I’ve been telling him to come up here and get out of the hurricane’s path, while he’s been stocking up on supplies and telling me he needs to be there to take care of the house.

Last weekend, Ellen and I traveled northward to Buffalo where Ellen was officiating at the 2nd wedding ceremony of two very dear men who wanted to marry under the newly-legal auspices of New York State. We joined them on a small boat that travels the famous lock-system of the Erie Canal. Ellen presided over the re-union of the two gentlemen while the boat was being lifted in a lock from one level of the canal to another. It was a beautiful, touching, incredibly loving celebration that, for many of us, was enhanced by the excitement, if not the symbolism, of rising up with the waters beneath us.

Last weekend, Ellen and I traveled northward to Buffalo where Ellen was officiating at the 2nd wedding ceremony of two very dear men who wanted to marry under the newly-legal auspices of New York State. We joined them on a small boat that travels the famous lock-system of the Erie Canal. Ellen presided over the re-union of the two gentlemen while the boat was being lifted in a lock from one level of the canal to another. It was a beautiful, touching, incredibly loving celebration that, for many of us, was enhanced by the excitement, if not the symbolism, of rising up with the waters beneath us. Part of the conversation taking place right now is how the city of Houston could have been so unprepared for the waters of Hurricane Harvey when, back in 2008, Hurricane Ike killed nearly a hundred people and caused $30 billion in damage. It was a dress rehearsal for Hurricane Harvey, and yet little was done in the years since. So while Houston has been experiencing incredible economic growth, it has also erased marshland after marshland, leaving few escape routes for the eventual floods that were coming. They were sitting ducks, they knew it, yet did nothing about it.

Part of the conversation taking place right now is how the city of Houston could have been so unprepared for the waters of Hurricane Harvey when, back in 2008, Hurricane Ike killed nearly a hundred people and caused $30 billion in damage. It was a dress rehearsal for Hurricane Harvey, and yet little was done in the years since. So while Houston has been experiencing incredible economic growth, it has also erased marshland after marshland, leaving few escape routes for the eventual floods that were coming. They were sitting ducks, they knew it, yet did nothing about it.

Housed in a tiny 50-seat performance space, this was part of an ongoing Shakespearean festival that required his cast and set to move in and out without much set-up or breakdown. So Aiden devised a strategy that eliminated the need for any set at all: the entire production was performed in darkness, ostensibly in a post-apocalyptic, underground future with flashlights their only source of illumination. Not merely practical, Aiden’s lighting strategy offered a powerful underscoring to Shakespeare’s extensive use of light imagery in his dialogue. Here are a few examples:

Housed in a tiny 50-seat performance space, this was part of an ongoing Shakespearean festival that required his cast and set to move in and out without much set-up or breakdown. So Aiden devised a strategy that eliminated the need for any set at all: the entire production was performed in darkness, ostensibly in a post-apocalyptic, underground future with flashlights their only source of illumination. Not merely practical, Aiden’s lighting strategy offered a powerful underscoring to Shakespeare’s extensive use of light imagery in his dialogue. Here are a few examples: And that’s where the truly special part of the eclipse began. First of all, everything I read leading up to Monday seemed to indicate that if you weren’t standing along the path of the complete eclipse why even bother looking up at all? Which is probably why she and I were among the very, very few at the airport in possession of the proper sunglasses. As we stood on the curb looking up at this incredible phenomenon (and don’t ever let anyone tell you that a partial eclipse isn’t worth watching), a police officer sauntered over to us. Before he could say, “Move along,” I said to him, “You know you want to look through our glasses.” And for the next twenty minutes or so, the three of us took turns not only viewing the eclipse but stopping others – airport employees and folks getting out of taxis – and inviting them to borrow our glasses as well. The best was stopping suspicious parents whose children pretty much snatched our glasses, their parents then excited to get a turn as well. We ended up gifting our entire set to a family that was grateful for our allowing them to enjoy this historic moment.

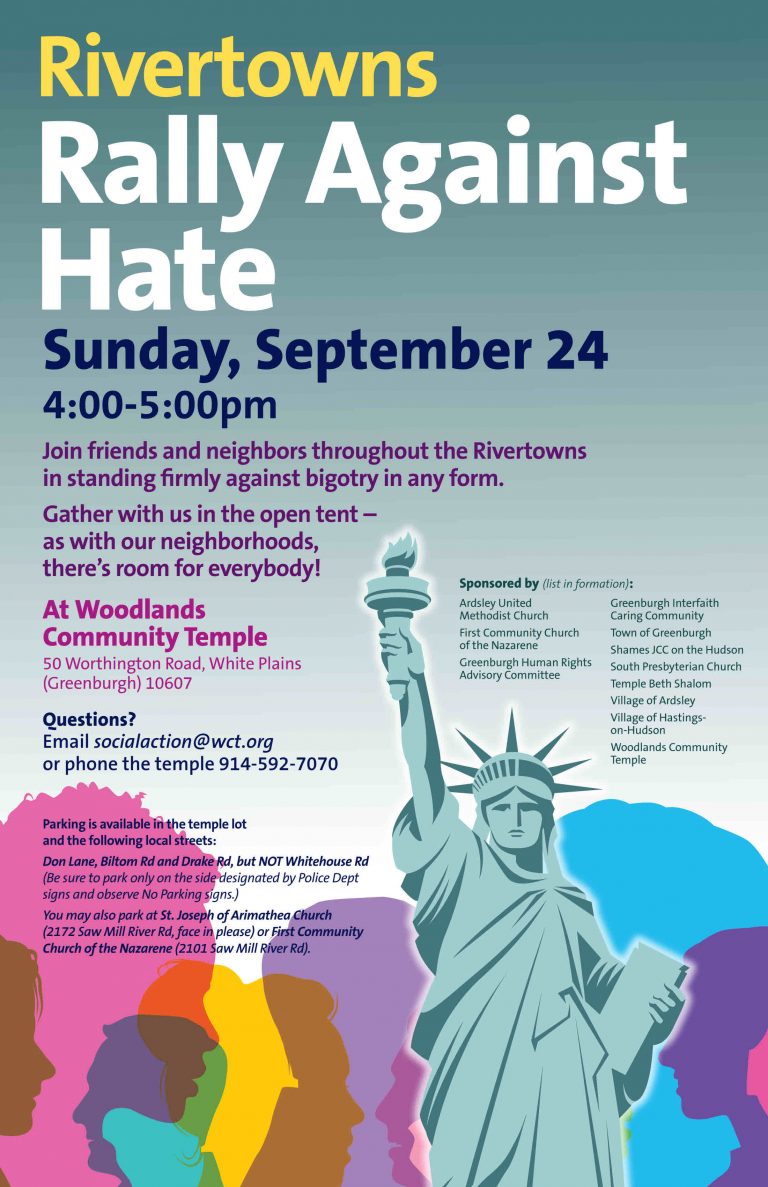

And that’s where the truly special part of the eclipse began. First of all, everything I read leading up to Monday seemed to indicate that if you weren’t standing along the path of the complete eclipse why even bother looking up at all? Which is probably why she and I were among the very, very few at the airport in possession of the proper sunglasses. As we stood on the curb looking up at this incredible phenomenon (and don’t ever let anyone tell you that a partial eclipse isn’t worth watching), a police officer sauntered over to us. Before he could say, “Move along,” I said to him, “You know you want to look through our glasses.” And for the next twenty minutes or so, the three of us took turns not only viewing the eclipse but stopping others – airport employees and folks getting out of taxis – and inviting them to borrow our glasses as well. The best was stopping suspicious parents whose children pretty much snatched our glasses, their parents then excited to get a turn as well. We ended up gifting our entire set to a family that was grateful for our allowing them to enjoy this historic moment. Here at Woodlands, we’ve begun a number of projects that you are welcome to join. Last night, we held our first gathering to learn how to accompany and support undocumented immigrants who have been detained by ICE. This is a non-violent, respectful, law-abiding path on which we can each stand in opposition to our nation’s brutal deportation surge. If this is the project that speaks to you, please come talk to me, or to Jonathan, or to Mara, or to our social action chairs, Roberta Roos and Joan Farber. We’d love to tell you more about it.

Here at Woodlands, we’ve begun a number of projects that you are welcome to join. Last night, we held our first gathering to learn how to accompany and support undocumented immigrants who have been detained by ICE. This is a non-violent, respectful, law-abiding path on which we can each stand in opposition to our nation’s brutal deportation surge. If this is the project that speaks to you, please come talk to me, or to Jonathan, or to Mara, or to our social action chairs, Roberta Roos and Joan Farber. We’d love to tell you more about it.

Eloheinu v’elohei avoteinu v’imoteinu … dear God and God of our ancestors … help us not only to understand that there are different ways to share opposing points of view, but to choose the way that is accompanied by respect and unyielding love. May we understand and acknowledge that those who advocate for that which we’d spend as much energy as we can to oppose, they love this country just as we do. We need not acquiesce but we certainly can listen and (like the rabbi who got the meaning of a song entirely wrong) realize that words spoken to us may feel misguided and hurtful, but these very words are expressing powerful feelings of the speaker’s fear and anxiety concerning what is felt to be an unpromising future for the world they love.

Eloheinu v’elohei avoteinu v’imoteinu … dear God and God of our ancestors … help us not only to understand that there are different ways to share opposing points of view, but to choose the way that is accompanied by respect and unyielding love. May we understand and acknowledge that those who advocate for that which we’d spend as much energy as we can to oppose, they love this country just as we do. We need not acquiesce but we certainly can listen and (like the rabbi who got the meaning of a song entirely wrong) realize that words spoken to us may feel misguided and hurtful, but these very words are expressing powerful feelings of the speaker’s fear and anxiety concerning what is felt to be an unpromising future for the world they love.