How I Spent My Summer Vacation

In case you didn’t know, it’s the Hebrew month of Elul. These are the four weeks leading up to the High Holy Days, a time when most Jewish families are thinking about, well, probably nothing having to do with the High Holy Days. Including this Labor Day weekend, it seems to be a time to squeeze out the very last minutes of summer fun and relaxation.

Rabbis and cantors, on the other hand, are pretty much thinking about nothing BUT the High Holy Days. There is music to prepare, sermons to be written, and a thousand other preparatory activities that must get done before any of you set foot in the tent next Sunday evening.

Rabbis and cantors, on the other hand, are pretty much thinking about nothing BUT the High Holy Days. There is music to prepare, sermons to be written, and a thousand other preparatory activities that must get done before any of you set foot in the tent next Sunday evening.

Let me give you one small example of how this season affects clergy. On Facebook (you know, where all serious work gets done), we Reform rabbis have a page all our own. It’s a place to discuss Torah, Talmud, and contemporary issues of import. This week, amidst the intense laboring to prepare our sermons, this most crucial posting was placed by a rabbi I know. He asked: What’s a “fun fact” that’s actually fun?

And that’s all it took. Dozens of rabbis, all with way more important things to do, began chiming in. Responses included:

• Ducks are the fastest flying birds.

• Your ears never stop growing.

• In Switzerland, it is illegal to own just one guinea pig.

• During our lifetime, each of us will produce enough saliva to fill two swimming pools.

• Escalators never actually break, they just become stairs.

I know you’re impressed by the width and breadth of knowledge that rabbis possess. You simply have no idea! By the way, I can’t verify that any of these are accurate, except maybe that broken escalators are stairs. I did learn that ducks are not the fastest flying birds. While the swiftest duck may clock in as high as 100 mph, the peregrine falcon flies double that!

All of this is to say: One never knows how someone is going to spend their summer vacation. Sure, there may be trips to exotic locales and sunbathing at the local pool, but those aren’t necessarily summer’s most indelible moments.

My summers, by the way, like yours, aren’t all vacation (tho I do remember those sublime years of youth when nothing needed to be accomplished between the last day of school in the spring and the first day back in the fall). My summer, slowed down as it was, included a half dozen funerals during which I was honored to share in the sacred act of saying goodbye to someone who was well-loved and will be much-missed. It’s always a privilege to be invited into these private, intimate, holy moments in people’s lives.

My summers, by the way, like yours, aren’t all vacation (tho I do remember those sublime years of youth when nothing needed to be accomplished between the last day of school in the spring and the first day back in the fall). My summer, slowed down as it was, included a half dozen funerals during which I was honored to share in the sacred act of saying goodbye to someone who was well-loved and will be much-missed. It’s always a privilege to be invited into these private, intimate, holy moments in people’s lives.

Other significant moments in my life this summer have included:

• Presiding over the demise of my kitchen stove and oven, during which Ellen and I had much fun picking out new appliances, but not quite so much fun having to spend lots of money hiring a carpenter to modify drawers and cupboards that no longer opened because the new units obstructed things deep inside our cabinetry. The lesson: Home ownership is really satisfying except when, like an aging body, it requires surprise visits and expenditures to keep things running.

• Speaking of which, earlier this summer I thought I was going deaf in one ear but, upon visiting the ENT doctor, I learned just how much wax can build up inside there. The lesson: Try to stop being so dramatic about physical demise. While we’re all definitely disintegrating, it’s probably happening at a much slower rate that we think.

• I got to visit my two now-pretty-well-grown children. Katie is married and an art educator living in Montpelier, Vermont. This summer, she returned to Eisner Camp after a 10-year hiatus, where she taught yoga, meditation and, of course, art. Aiden has gone what they call “adulting,” moving to Denver this summer, getting himself five part-time jobs, an apartment, and even a new dentist! The lesson: All that love we gave our kids when they were young? It really does serve as the foundation for them building lives that are vibrant, healthy and satisfying. And I have to say, I’m happier for my kids now than any report card or school concert ever made me feel!

• Lastly, bringing it all together, there’s Mars. Throughout June, July and August, the red planet came nearer to our earth than usual. Mostly residing about 140 million miles from Times Square, this summer Mars almost made it all the way up to Westchester, coming 100 million miles closer than ever! But what was most profound for me was that no matter where I was this summer: Massachusetts, Colorado or New York, there was Mars, shining brilliantly in the night sky. The lesson: Everything is connected, no one is alone, and we are all part of the same magnificent, unfolding story.

• Lastly, bringing it all together, there’s Mars. Throughout June, July and August, the red planet came nearer to our earth than usual. Mostly residing about 140 million miles from Times Square, this summer Mars almost made it all the way up to Westchester, coming 100 million miles closer than ever! But what was most profound for me was that no matter where I was this summer: Massachusetts, Colorado or New York, there was Mars, shining brilliantly in the night sky. The lesson: Everything is connected, no one is alone, and we are all part of the same magnificent, unfolding story.

So while, yes, the White House continues to give us reasons to wonder if civilization is rapidly coming to an end, there remains so much that is good in our world. And even while we fret – concerned for immigrant children still living apart from their parents, Russian meddling in our democratic elections, genocide in Myanmar, North Korea’s nuclear weapons, and rampant gun violence – we can also rejoice – 12 boys and their coach successfully rescued after 17 days stuck in a cave in Thailand, the World Cup bringing us all together in global competition marked by shared friendship and excitement that transcended all ethnic and nationalist demarcations and, since the year 2000, 1.2 billion additional human beings on the planet have gained access to electricity, one of the first steps out of poverty.

There is still much reason to rejoice.

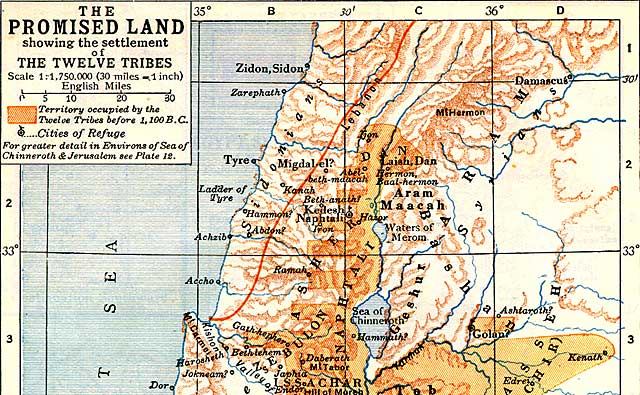

In this week’s parasha, Kee Tavo, we read (in Deut 26:11) Moses’ instructions to the Israelites as they prepare to conclude their 40 years of desert wandering and enter the Promised Land: “V’samakhta v’khol ha’tov asher natan lakh … you shall enjoy, together with the Levite and the stranger in your midst, all the bounty that God has bestowed upon you and your household.” This foundational value, shared as they readied themselves to go to war, serves as a profound reminder to us that human existence isn’t for the purpose of suffering; it’s to build lives that mean something, that provide sustenance and safety for all people, and ultimately to love and to laugh and to luxuriate in the simple joys of being able to have a place to live, enjoy one’s family, and even to chuckle at fun facts shared while avoiding matters of responsibility.

So I’ll leave you with two more fun facts and a wish.

1st fun fact: Banging your head against a wall for one hour burns 150 calories.

My wish: There are an infinite number of ways that we can spend the time allotted to us on this earth. Some of it should be spent helping make things better for everyone. And some of it should probably be spent fretting about how bad things are. But not only is it vital that we spend time with people we love and in activities we love, we ought also avoid, as much as possible, uselessly banging our heads against a wall, even if someone tries to convince us there’s a benefit in it.

The Israelites understood that joy was a fundamental component to life, and that all are commanded to enjoy, and to ensure others can do the same. From the dawn of Creation, a bounty has been bestowed upon us. It would be mean-spirited to squander that.

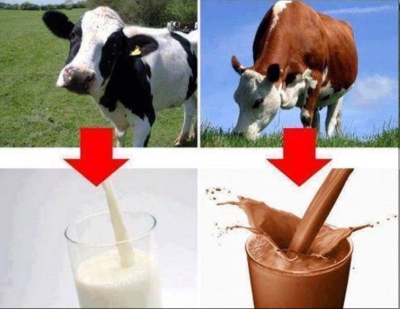

2nd fun fact: 7% of all Americans actually believe that chocolate milk comes from brown cows. I don’t know if that’s true, but I’d bet it wouldn’t surprise many of you to learn it is (the 7% believing, I mean). This big, beautiful world of ours is filled with the full spectrum of humanity, including a few (what’s 7% of 325 million?) who think some pretty strange stuff. As the month of Elul nears its finishing line and we prepare to meet in the tent next Sunday to greet the New Year, may we embrace all of our human family, chuckling at those who subscribe to fun facts that are much more fun than fact, all the while extending our love and our compassion even to those from whom we differ immensely. Let’s resolve to make this New Year 5779 one of goodness, kindness, understanding, and the simple delight that comes from sharing the most magnificent fun fact of all: life.

2nd fun fact: 7% of all Americans actually believe that chocolate milk comes from brown cows. I don’t know if that’s true, but I’d bet it wouldn’t surprise many of you to learn it is (the 7% believing, I mean). This big, beautiful world of ours is filled with the full spectrum of humanity, including a few (what’s 7% of 325 million?) who think some pretty strange stuff. As the month of Elul nears its finishing line and we prepare to meet in the tent next Sunday to greet the New Year, may we embrace all of our human family, chuckling at those who subscribe to fun facts that are much more fun than fact, all the while extending our love and our compassion even to those from whom we differ immensely. Let’s resolve to make this New Year 5779 one of goodness, kindness, understanding, and the simple delight that comes from sharing the most magnificent fun fact of all: life.

That’s how I spent my summer vacation.

Ketivah v’khatimah tovah … may all soon be inscribed for blessing and peace. Shabbat shalom.

Billy

While preparing dinner, mom asked her child to go into the pantry and fetch a can of tomato soup. But the little boy wouldn’t go in alone, saying, “It’s dark in there. I’m scared.” To which his mom responded, “God will be in there with you. Now you go and get a can of tomato soup.” So Johnny stood up, went to the door of the pantry and, peeking inside, saw how dark it was but got an idea. “God,” he said, “if you’re in there, would You hand me that can of tomato soup?”

While preparing dinner, mom asked her child to go into the pantry and fetch a can of tomato soup. But the little boy wouldn’t go in alone, saying, “It’s dark in there. I’m scared.” To which his mom responded, “God will be in there with you. Now you go and get a can of tomato soup.” So Johnny stood up, went to the door of the pantry and, peeking inside, saw how dark it was but got an idea. “God,” he said, “if you’re in there, would You hand me that can of tomato soup?” A short while after the Golden Calf is built, Moses does indeed come down Mount Sinai. He’s carrying with him a tremendous gift: the Tablets of the Covenant. The Torah. But when he sees how the Israelites have abandoned God and their ideals, he too loses faith and hurls. He hurls the Tablets to the ground, smashing them into useless shards.

A short while after the Golden Calf is built, Moses does indeed come down Mount Sinai. He’s carrying with him a tremendous gift: the Tablets of the Covenant. The Torah. But when he sees how the Israelites have abandoned God and their ideals, he too loses faith and hurls. He hurls the Tablets to the ground, smashing them into useless shards. Eloheinu v’elohei avoteinu v’imoteinu … dear God and God of our ancestors … it can get tough to believe in You. From time immemorial when our lives have taken hard hits, many of us have lost our faith. Our ideals too. When things get tough, some of us grow cynical, tighten ranks, and look out for number one. But together, we can be tougher than that. So please, hang with us while we stumble through hard times. Help us keep our ideals. Stick with us as we work to stay true to the values You taught us, values we’ve always loved and by which we’ve tried to live. And may we help our beloved nation remain steadfast in its commitment to the ideals on which it was founded. A little girl may have said it best, “God is my shepherd, that’s all I want.” May Your gifts from days-of-old continue to guide us in building lives that bring blessing to ourselves, to our loved ones, and to all the world.

Eloheinu v’elohei avoteinu v’imoteinu … dear God and God of our ancestors … it can get tough to believe in You. From time immemorial when our lives have taken hard hits, many of us have lost our faith. Our ideals too. When things get tough, some of us grow cynical, tighten ranks, and look out for number one. But together, we can be tougher than that. So please, hang with us while we stumble through hard times. Help us keep our ideals. Stick with us as we work to stay true to the values You taught us, values we’ve always loved and by which we’ve tried to live. And may we help our beloved nation remain steadfast in its commitment to the ideals on which it was founded. A little girl may have said it best, “God is my shepherd, that’s all I want.” May Your gifts from days-of-old continue to guide us in building lives that bring blessing to ourselves, to our loved ones, and to all the world.

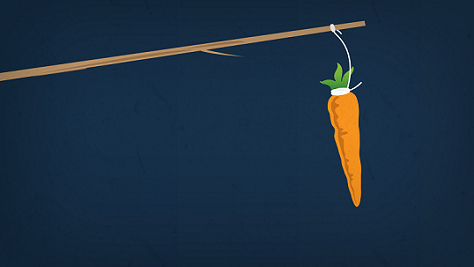

And with that deeply philosophical question which confronts our awareness that something may not be true and yet we cling to the possibility that perhaps it is, Tyler Levan touched upon a debate that has dogged humankind since our brains brought us out of the trees. Religion used to make excellent and effective use of fear to get people to live morally upright lives. The formula was a simple one: do God’s mitzvot and receive God’s reward; stray from God’s mitzvot and prepare to meet thy doom. Such “understanding” of how the world works used to go unquestioned, and many behaved better because of it. Today, we may have great difficulty believing in the doctrine of reward and punishment, but we sure wish it were real.

And with that deeply philosophical question which confronts our awareness that something may not be true and yet we cling to the possibility that perhaps it is, Tyler Levan touched upon a debate that has dogged humankind since our brains brought us out of the trees. Religion used to make excellent and effective use of fear to get people to live morally upright lives. The formula was a simple one: do God’s mitzvot and receive God’s reward; stray from God’s mitzvot and prepare to meet thy doom. Such “understanding” of how the world works used to go unquestioned, and many behaved better because of it. Today, we may have great difficulty believing in the doctrine of reward and punishment, but we sure wish it were real. You may be saying to yourself, “I didn’t know Judaism believes in heaven and hell?” The short answer is yes, we do. What those two things look like, nobody pretends to know. Jewish thinkers and writers throughout the ages have toyed with these concepts, but the rabbis only settle upon this admonition, “Just observe the mitzvot. Be careful how you live your life in this world and the world-to-come will take care of itself.”

You may be saying to yourself, “I didn’t know Judaism believes in heaven and hell?” The short answer is yes, we do. What those two things look like, nobody pretends to know. Jewish thinkers and writers throughout the ages have toyed with these concepts, but the rabbis only settle upon this admonition, “Just observe the mitzvot. Be careful how you live your life in this world and the world-to-come will take care of itself.” It may just be my greatest statement of faith, but I absolutely believe that goodness abounds, that while temptation and perhaps fear can drive us to act contrary to what we know is right, most of us try to do the right thing. And not just because it’s right, but because we like doing good. And I suppose my other great statement of faith is that I believe these things come back to us. They come back in the respect we engender within ourselves. They come back in the admiration and love we receive from others who observe our kindnesses. And maybe they even come back in a loving universe that appreciates the good we’ve done and tries to offer some good in return.

It may just be my greatest statement of faith, but I absolutely believe that goodness abounds, that while temptation and perhaps fear can drive us to act contrary to what we know is right, most of us try to do the right thing. And not just because it’s right, but because we like doing good. And I suppose my other great statement of faith is that I believe these things come back to us. They come back in the respect we engender within ourselves. They come back in the admiration and love we receive from others who observe our kindnesses. And maybe they even come back in a loving universe that appreciates the good we’ve done and tries to offer some good in return.

That’s why we have a night each year to thank our teachers. You — our religious school faculty and adult education faculty — bring us vibrant, passionate, often entertaining presentations that engage us in challenging exercises to help us determine the kind of people we want to be. And with your guidance, we’ll hopefully progress in our abilities to be good, decent, and caring.

That’s why we have a night each year to thank our teachers. You — our religious school faculty and adult education faculty — bring us vibrant, passionate, often entertaining presentations that engage us in challenging exercises to help us determine the kind of people we want to be. And with your guidance, we’ll hopefully progress in our abilities to be good, decent, and caring.

It was back in 2006 that Jay Leno observed what he called “positive news” from out of Israel. “Both sides are signing off on [President Bush’s] road map to peace,” Leno said. “The bad news is the Israelis think the road goes through the West Bank, Palestinians think it goes right through downtown Jerusalem.”

It was back in 2006 that Jay Leno observed what he called “positive news” from out of Israel. “Both sides are signing off on [President Bush’s] road map to peace,” Leno said. “The bad news is the Israelis think the road goes through the West Bank, Palestinians think it goes right through downtown Jerusalem.”