Munich 1972: Remembering for a Blessing

A story is told of Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Kotzk, the Kotzker rebbe (early 1800’s). The Kotzker once invited the distinguished Rabbi Yehiel Meir of Gostinin to blow the shofar in his synagogue. Rabbi Yehiel Meir came up to the bimah, picked up the shofar, pursed his lips, and lifted the shofar to his mouth. The Kotzker rebbe cried out, “Tekiya,” and, horror of horrors, Rabbi Yehiel Meir was suddenly struck with a case of dry-mouth. We’ve all seen it happen. He blew into the shofar, his face turned red, his eyes bulged out, and to what end? A little tiny peep of a tekiya was all that was heard.

A story is told of Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Kotzk, the Kotzker rebbe (early 1800’s). The Kotzker once invited the distinguished Rabbi Yehiel Meir of Gostinin to blow the shofar in his synagogue. Rabbi Yehiel Meir came up to the bimah, picked up the shofar, pursed his lips, and lifted the shofar to his mouth. The Kotzker rebbe cried out, “Tekiya,” and, horror of horrors, Rabbi Yehiel Meir was suddenly struck with a case of dry-mouth. We’ve all seen it happen. He blew into the shofar, his face turned red, his eyes bulged out, and to what end? A little tiny peep of a tekiya was all that was heard.

Rabbi Yehiel Meir was crestfallen. After the service was over, the Kotzker rebbe came over to Rabbi Yehiel Meir and said, “Yasher Koach on your shofar blowing!” Yehiel Meir replied, “Rebbe, I know my playing wasn’t very good, but how can you make fun of me for it?” To which the great Kotzker rebbe responded, “Yehiel Meir. My friend. When a great person blows the shofar, even the tiniest peep of a tekiya is considered to be like the voices of the heavenly choir.”

Is that not our wish for all of living?

The quality of a tekiya is to be found not in the strength and clarity of the note, but rather in the strength of character and clarity of purpose which the baal tekiya, the shofar blower, pours into his labors. So too, the spirit and passion that go into our life’s efforts are far more important than any individual results. We applaud one another for being brave enough to pick up the shofar of our lives, to step up and give all we’ve got to adding our sound to the harmony of voices endeavoring to bring beauty and purpose into our world. Our tekiya may only be a peep … but, at that moment, it will be enough.

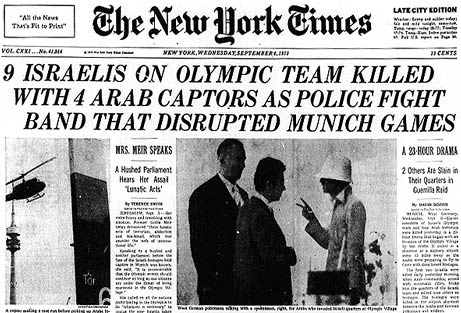

Forty years ago this past Tuesday (September 4), eleven athletes representing the state of Israel were brutally murdered by terrorists infiltrating the Munich Olympics in 1972. The Olympic Village had been specifically created to encourage an open and friendly atmosphere for the express purpose of counterbalancing memories of the militaristic image of the 1936 Olympics held in wartime Germany. Athletes easily came and went, allowing the terrorists to do so as well. German authorities had actually received a tip from a Palestinian informant three weeks beforehand, but the tip wasn’t acted upon, with disastrous results.

Forty years ago this past Tuesday (September 4), eleven athletes representing the state of Israel were brutally murdered by terrorists infiltrating the Munich Olympics in 1972. The Olympic Village had been specifically created to encourage an open and friendly atmosphere for the express purpose of counterbalancing memories of the militaristic image of the 1936 Olympics held in wartime Germany. Athletes easily came and went, allowing the terrorists to do so as well. German authorities had actually received a tip from a Palestinian informant three weeks beforehand, but the tip wasn’t acted upon, with disastrous results.

Forty years later, we’re asked what to do with these memories. During the London Olympics, requests for a minute of silence to honor the Israelies who died in 1972 were denied. So thousands of minutes were observed across the globe instead.

Tonight, we also observe the yahrzeit for those who died in the events of Sept 11, 2001. Eleven years after that tragic day, we’re still asking ourselves how to remember. With the opening of the 9/11 Memorial down at the World Trade Center, part of that question has been answered. But the larger question remains: Painful memories exist for us all. What do we do with those memories? Is it possible to honor them without letting them define us? Can we sing our songs of joy even while shedding tears of loss?

Tonight, we also observe the yahrzeit for those who died in the events of Sept 11, 2001. Eleven years after that tragic day, we’re still asking ourselves how to remember. With the opening of the 9/11 Memorial down at the World Trade Center, part of that question has been answered. But the larger question remains: Painful memories exist for us all. What do we do with those memories? Is it possible to honor them without letting them define us? Can we sing our songs of joy even while shedding tears of loss?

In this weekend’s Torah reading, Kee Tavo, we encounter a passage that’s familiar to us all:

When you enter the land that God is giving you, take some of first fruits which you harvest, carry them to God’s temple, give them to the kohen in charge and say to him, “My father was a fugitive Aramean. He went down to Egypt with meager numbers and sojourned there, and in time became a great and populous nation. The Egyptians dealt harshly with us and oppressed us, imposing heavy labor upon us. We cried out to the God of our fathers and mothers, who heard our plea and witnessed our misery. Then God freed us from Egypt by a mighty hand, by an outstretched arm and awesome power, bringing us to to a land flowing with milk and honey. (Deut 26:1-9)

Contained in these words, I believe, is the answer to our question of what to do with painful memories. Surely, the years of Egyptian enslavement were as brutal as any experienced by a subjugated people. Three thousand years later, we could still harbor resentment and bitterness for the treatment accorded our ancestors. But our tradition chose differently. Instead of resentment, we chose to adopt a philosophy and lifestyle that took note of injustice anywhere – not merely within our own communities – and that tradition has challenged us to act for fairness and peace.

Three thousand years later, the descendants of those Israelite slaves stood on the front lines of the battle for racial equality in the 1950s and 60s, they stood on the front lines of the battle for gender equality in the 1970s, and they now stand on the front lines of the battle for LGBT equality today.

We don’t merely stand up for religious freedom for Jews, but religious freedom for Muslims and Sikhs and Christians.

And while we stand up for Israel’s right to live in peace, we yearn for her neighbors, the Palestinians, to know peace as well – not simply because that would be good for Israel, but because it would be good for Palestinian children, and Palestinian grandparents, and Palestinian moms and dads, too.

And while we stand up for Israel’s right to live in peace, we yearn for her neighbors, the Palestinians, to know peace as well – not simply because that would be good for Israel, but because it would be good for Palestinian children, and Palestinian grandparents, and Palestinian moms and dads, too.

The 19th century author and Unitarian minister Edward Everett Hale wrote: “I cannot do everything, but still I can do something; and [just] because I cannot do everything, I will not refuse to do the something that I can do.”

Forty years ago, eleven young men were murdered because of the heritage they share with you and me. Three thousand years ago, something a lot like that happened in ancient Egypt. And so it has gone throughout history. But like the tiny but mighty peep that emerged from Rabbi Yehiel Meir’s shofar, we will not relinquish our passion for life, our passion for justice, because of pervasive injustice. Instead, so long as we are able, we will do as much good as we can – for one another, for our neighbors, even for those who are not yet our friends.

Why? Because we know what it’s like to feel the sting of the whip, the butt of the rifle. And no matter what, our commitment to creating a world that is just and fair and kind will never flag.

This is what a synagogue is all about. If you happen to be looking for one, make sure it’s not too easy to belong, that it challenges you, along with building a strong life and family, to build a strong community and a strong world, as well.

margosmidrash

pretty inspiring, especially our voices adding harmony to bring beauty and purpose to the world. and seeking the challenge. L’shanah Tovah to you and yours, R. Billy!