Love Is a Many-Splendored Thing

Zeke and May had been married for over seventy years. Zeke was 101 years old and his wife was 99. One hot afternoon, as they sat together on their front porch rocking away, the old man, who was nearly deaf, couldn’t quite hear when May looked over at him and with admiration in her eyes said, “Zeke, I’m proud of you.” “What’s that you said, May?” She raised her voice and shouted in his direction, “I’m proud of you!” To which Zeke nodded and replied, “I’m tired of you too, May.”

Zeke and May had been married for over seventy years. Zeke was 101 years old and his wife was 99. One hot afternoon, as they sat together on their front porch rocking away, the old man, who was nearly deaf, couldn’t quite hear when May looked over at him and with admiration in her eyes said, “Zeke, I’m proud of you.” “What’s that you said, May?” She raised her voice and shouted in his direction, “I’m proud of you!” To which Zeke nodded and replied, “I’m tired of you too, May.”

Twenty-nine years a rabbi now, it’s hard for me to say just how many hundreds of wedding ceremonies I’ve presided over. I’ve used this story at only a couple of them. But what I can tell you is that I’ve loved being part of each and every one of those ceremonies. Many have been for kids I’ve watched grow up here, which has been very sweet indeed, while others have been for couples I’ve loved meeting and sharing in the excitement of their passionate and profound commitment to each other. And trying not to spoil their fun too much as I counsel them about the imperiled existence awaiting them just up ahead.

Tonight, being two days before Valentine’s Day, we’ve already listened to some of our fellow congregants share iyyunim on the theme of love. And as we’ve heard, love can encompass far more than a life-partner. Children, pets, even summer camp, can be among the many recipients of our heart’s devotion.

The human heart may occupy just a few meager ounces of space, but its capacity for love is possibly infinite. I asked myself the question – “What do I love?” – just to try and gauge my own heart’s capacity a little bit. I came up with a starter list that includes: my wife, my family, my work, this temple, my music (most music!), food (tho definitely not all food), nature, spending time in nature, reading books, apparently real books since I don’t enjoy Kindles, learning (especially Jewish learning), hi-tech gadgetry, compassion and generosity, smart people who have important things to say, and smart people whose important things that they say are effective and (even better) caring.

Oh, and my dog.

I’m sure I could quadruple this list if I spent more time on it. Which reminds me, let me add “time” to my list. I adore time!

This expanding of the list of what we love interests me. Not just our capacity to love, but our ability to expand that capacity, and to change how we feel. To add new items to the list. And most interesting of all, our capacity for adding items that we may have previously rejected, or even spurned. This, I think, is where we get Jewish about it.

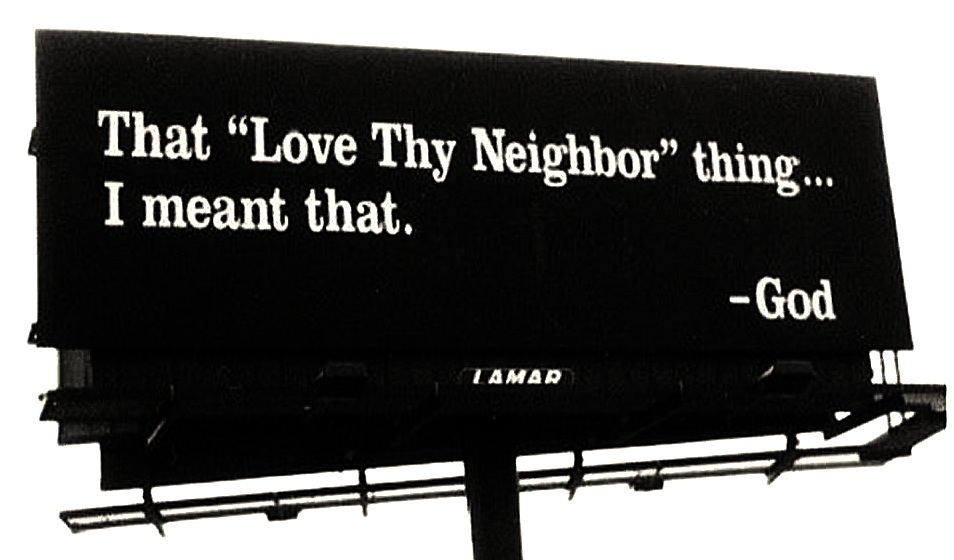

One of the most fundamental texts in Jewish tradition about love is found in the book of Leviticus. In chapter 19, which is also known as the Holiness Code, we read: V’ahavta l’reyakha kamokha … love your neighbor as yourself.

Leave it to Judaism, of course, to offer such a fundamental commandment but make it next to impossible to fully understand. I mean, it looks simple. Love others! But what’s it really telling us? Love your neighbor as much as you love yourself? Love your neighbor in the same way you love yourself? And what if you don’t love yourself – are you allowed to treat others that way too?

The Hebrew kamokha, “as yourself,” can also be understood as “love the neighbor who is like yourself.” What does that mean? That people who are not like us, we don’t have to love them? Or is the Torah saying that it’s actually harder to love those who are similar to ourselves? You know, the guy at work who does pretty much what you do, so you kind of hope he fails. The woman who plays the same musical instrument as you – you’re so much better than she is. Or family, with whom we spend so much time that the opportunities for disappointment and resentment loom large. Moses Maimonides presumed this mitzvah was referring to how we treat other Jews. Which leaves us with a different question: Was the Rambam telling us that our responsibilities for love go no further than how we treat other Jews? Or is that just the place where love must begin?

And then to get weird, the Talmud understands “Love your neighbor as yourself” as meaning, “Choose for him a good death.” I mean, yes, I do want to have a good death … someday … but how did they figure this is the particular thing that God was talking about when we were commanded to love our neighbor as ourself? On the other hand, dying is among our most vulnerable experiences; we entirely rely on others to help us die. Perhaps that is indeed one of life’s most loving moments, when we make sure that a loved one can die in comfort and in peace.

One 15th century commentator, Isaac ben Moses Arama, suggested we look to the friendship between David and Jonathan. David was aspiring to become the king of Israel and Jonathan was the son of the current king, Saul, which either complicated Jonathan’s relationship with David or his relationship with his dad the king. A passage in the Mishna (Avot 5:16) reads, “Any love that is dependent on something, when that something goes away, so too does the love. While any love that is not dependent on something, it will never perish. That,” the Mishna concludes, “is the love of David and Jonathan.”

In our Book of Samuel class, we happened to have just read those passages. And while I can’t vouch for the depth of David’s love, Jonathan’s did indeed seem awesomely powerful. As the son of Saul, Jonathan was the crown prince, and he had every reason to be resentful of David’s aspiration to power, an upward trajectory that would prevent Jonathan from succeeding his father. And yet, not once does that factor into his words or deeds. Jonathan loves David, and nothing – even the loss of his kingship over Israel – would jeopardize those feelings.

I imagine that for 99.9% of the human population, love takes hard work and sturdy blinders. Which is why Jonathan is view with such awe by our tradition. I’ve been married to Ellen for 34 years. What that woman has had to put up with, it’s remarkable she didn’t kick me out decades ago.

It reminds me of a husband and wife who had been married for sixty years and had no secrets except for one. The woman had kept a shoebox in her closet that forbade her husband from ever opening it. When she grew very old and near to dying, she gave her husband her blessing to finally open the box. Inside, he found a crocheted doll and $95,000 in cash. His wife explained, “My mother told me that the secret to a happy marriage was never to argue. Instead, I should keep quiet and crochet a doll.” Her husband was deeply touched. After sixty years, whe corcheted only one doll? “But what’s all this money?” he asked. “Oh, that,” she said, “that’s the money I made from selling dolls.”

I am continually amazed at relationships that stand the test of time. I know that there’s so much more to them than the good times that were enjoyed together in the beginning and felt like the basis for staying together forever. I know that when real life gets added into the mix, and love still manages to remain, something very special, and very inspiring, has taken place.

Which brings me to the question of expanding our capacity to love to include what we may have previously rejected, or even spurned.

Many years ago, where Pumpernickel is in Ardsley, there used to be a restaurant called Tokyo Seoul. Our family loved eating there and went often. At the beginning of the meal, the server would place a number of small dishes in front of us, each containing a taste of some Asian hors d’oeuvres. One of these dishes contained kimchi, a fermented Korean cabbage that packed quite a spicy wallop. I didn’t much care for kimchi, but each time we went I ate a small bit of it. Over time, and I’m talking years here, I was able to increase the amount of kimchi I could tolerate. And today, I love it. I can sit with a full jar and just snack away!

V’ahavta l’reyakha kamokha … love your neighbor as yourself.

V’ahavta l’reyakha kamokha … love your neighbor as yourself.

What if you just don’t like them? What is they’re like an off-putting kimchi? Well, unless you subscribe to the notion that we’re commanded only to “love your neighbor who is like yourself,” our tradition doesn’t offer much of a way out. Either we perform the mitzvah, or we don’t.

When I was in college, I remember a fellow student who just rubbed me the wrong way. Our paths crossed many times during our years there, but I never gave her the time of day. For more than three decades, I carried that with me – not one of my prouder chapters. But a few years ago, I found her. And even though she now lives in the part of the world that invented kimchi, and I didn’t ever have to have anything to do with her again, I remembered that I’m Jewish and I’m supposed to try and live by at least some of the mitzvot. So I reached out to her, started a very long-distance correspondence and then spent some time together in-during a visit to the States. And you know what? It’s remarkable how much nicer she is thirty-five years later. Or could that be me? Well, either way, I’ve got a new pen-pal. And on a whole bunch of levels, it feels really good.

Which brings me to one more example – it’s of a completely unexpected love that came from a place of pure malice and hostility. I’ll never forget this story of a neo-Nazi by the name of Larry Trapp. In the early-90s, he was a Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan who harassed a cantor by the name of Michael Weisser, threatening to blow up his temple in Lincoln, Nebraska. But Cantor Weisser responded in an extraordinary way. He reached out to Trapp with compassion and with a challenge: to talk with him, and to learn about the religion and the people he hated so deeply. In time, this neo-nazi befriended the cantor, and ended up converting to Judaism and joining the cantor’s synagogue.

I think that of all the love there is in the world, nothing could be sweeter than that of an enemy who becomes a friend. It is the most idealistic work for any of us to incorporate into our lives. It takes tremendous courage, and probably more than a little bit of stubbornness and chutzpah. I suspect that such attempts fail as often as they succeed, but all such efforts are noble ones. And when they do succeed, as with this one, their stories are unforgettable.

But I take it back – that may not be the greatest love. There is little doubt in my mind that the greatest love may very well be the one where – across huge tracts of time and even more moments of disappointment – individuals, or groups, manage to stick it out with one another. Despite letting each other down, neither walks away. I’m thinking of alliances between nations, or between disparate communities, among lifelong friends, relatives and, of course, between husbands and wives, between life-partners. Rabbi Larry Hoffman teaches about the honor of showing up each day to life. It’s hard enough when life settles into the ordinary and we wonder if that’s all there is. But then, when it gets rocky, to not walk away, to stick around and work things out if at all possible, that may be the highest fulfillment of v’ahavta l’reyakha kamokha.

So on this nearly-Valentine’s Day Shabbat, three cheers for love. Wherever it surfaces, however it steals our hearts, love is where it’s at. Zeke may have expressed an unfortunate truth in telling May he was tired of her too, but I’m guessing that he had no intention of going anywhere without her by his side. So in whatever form your Valentine appears this year, I hope that will be the same for you as well.

Don’t forget to bring home flowers!

The late-19th century writer Shalom Aleichem was a funny guy. He once wrote, “I never went to the fair without taking into consideration the feelings of my neighbors. If I was successful and peddled everything I took, and came home with my pockets stuffed with money, and my heart singing, I would tell my neighbors that I had lost all my money and was a failed man. The outcome of this was that I was happy and my neighbors were happy.”

Elohenu v’elohey avoteynu v’imoteynu … dear God and God of our ancestors … help us to better understand our family and our neighbors. Teach us to care about them kamokha, somewhere in the vicinity of the way we care for ourselves. Give us a “stick-to-it-ness” that will help us to ride out the rockier moments of our relationships. And expand the capacity of our hearts so that we might expand the list of those included in the sharing of our love. It’s cost-effective, fits any budget, and goes a long way to fulfill that long list of mitzvot You gave us at Mount Sinai.

Happy Valentine’s Day!

Leave a Reply