Mentors

The big news for me this week was the resignation of Dr. Brenda Fitzgerald, Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It appears that not only did her personal investments present a conflict of interest – not cool for one of this nation’s top health officials to be picking health stocks that make it appear as if she’s got an inside track on where to make money – but she was also investing in tobacco companies! The head of our nation’s leading national public health advocate is fine building her nest egg on the backs of people suffering from lung cancer, emphysema, heart disease, loss of vision, and stroke.

Now, in all fairness to Dr. Fitzgerald, she probably knew that I was going to speak about mentors this week and sacrificed herself to provide us with a stellar example of how not to be a role-model for others.

By the way, lest you should think Dr. Fitzgerald’s gaffe was a fluke, she also took a one million dollar kickback from the Coca-Cola company for following their sage advice in battling childhood obesity, adopting an idea from the soda giant’s playbook that exercise, not calorie control, is the key to weight loss. Thank you, Doctor, for taking the high road on that one.

A mentor of course, as we have been hearing from others this evening, is someone whose knowledge and experience provides invaluable wisdom and guidance to us as we do the work to excel in a particular area of life that’s important to us.

In this week’s Torah parasha, we meet Yitro (Jethro), who is a Kenite shepherd and a Midianite priest. His daughter Tzippora was one of seven sisters being harassed at a local well when the taskmaster-slaying Moses happened along as he was fleeing from Egyptian authorities and intervened on the sisters’ behalf. Moses was subsequently taken home to meet dad, Moses and Tzippora were wed, and the rest (as they say) is ancient history.

In Exodus 18, we learn why Jethro is well-known for his wise counsel to Moses. First, after Moses left behind his wife and children to take a new job freeing the Israelites from slavery, it was Jethro who brought Moses’ family to him. Wise counsel #1: Almost nothing is so important in life that leaving behind one’s family becomes the right thing to do.

Jethro then remained for a while with Moses and his wandering Israelites. He noticed that in addition to guiding more than a half million people into freedom, Moses would stop to adjudicate individual grievances among the people. Wise counsel #2: Jethro talked some sense into Moses, convincing him to do a little delegating and to appoint some very bright underlings to take on these important but distributable tasks, conserving his own energy to complete those responsibilities for which he had been hired.

It was these two acts that secured Jethro’s high regard in the annals of our people’s history. For two millennia, whenever we have looked for role-models in the Torah, Jethro has ranked high on the list.

My choice to become a rabbi was, I’m a bit chagrined to report, not the result of having a mentor in my childhood whom I respected and admired. Quite the opposite, I’m afraid. I was never comfortable with my rabbi, never felt warmth from him, and rather disliked the man. In all fairness, I need to tell you that my older sister adored him, thought he was one of the smartest and wisest people on the planet, and loved learning with him and listening to his sermons. When I was growing up, all I could think was, “There must be a better way to be a rabbi.” And that was a big part of what motivated me to attend rabbinical school. He had been for me a negative mentor, ultimately guiding my choice of career, but only because he showed me what I didn’t want to be, and what I didn’t want to impose on others.

This happened, I’m sorry to report, in rabbinical school as well.

When I was studying to become a rabbi, I had many classes in the subjects that comprise rabbinic training: Hebrew, Aramaic, Bible, Talmud, Theology, Philosophy and Jewish History. Some of the greatest minds of our time held office hours in that building down at One West Fourth Street in Manhattan. But when I think about how some of these giants of Jewish thought treated me and my fellow students during those five years, I’m amazed the institution lacked a better understanding of what they were trying to produce in the rabbis, cantors and educators they would be providing to the Jewish community. I wasn’t one of the student body’s most promising intellects, but I was trying to be a good guy who would emerge from HUC with enough tools to be a good rabbi as well. So when professor after professor criticized me for not rising to the level of my more brilliant co-students, I thought, “Well, here’s a familiar kind of mentoring. Help me become the best I can be by showing me what I most definitely don’t want to be.”

Dr. Chernick and Dr. Kravitz

Now, HUC wasn’t completely bereft of positive role models. Here are two of them.

I struggled greatly to understand what my Talmud professor, Dr. Michael Chernick, was teaching us. Dr. Chernick was an Orthodox rabbi who had dedicated his career to training Reform rabbis, and it was his kindness – his patience with me – that rose high above his Talmudic genius. By the time I was ordained, I knew I wanted to teach Talmud simply because he did.

Then there was Dr. Leonard Kravitz. With him, I studied Maimonides, Medieval Jewish Philosophy, and how to write sermons. He too was one of these super-brilliant guys who often left me way behind as he waxed poetic about arcane Jewish ideas. But his worst critiques of my work were far more encouraging than others’ best appraisals. I remember when we wrote practice-sermons for Dr. Kravitz, and the most devastating criticism I received – and I received it often – was for him to write, “Mr. Dreskin, you have many good ideas here.” Instead of slamming me for artless rambling in my thinking, he suggested I use the sermon as the basis for ten others. I could handle that. And today, I’m pretty sure I’m a better writer because of him. But here’s what I know for sure: I’m a better human being because of him. Without fail, Dr. Kravitz displayed each and every day an unshakeable commitment to good will, gracious dialogue, affectionate support, and a sense of humor that disarmed everybody and let us know that he was on our side.

Now lest you think I’m nothing but a hyper-critical grump, I have had some positive role-models in my life.

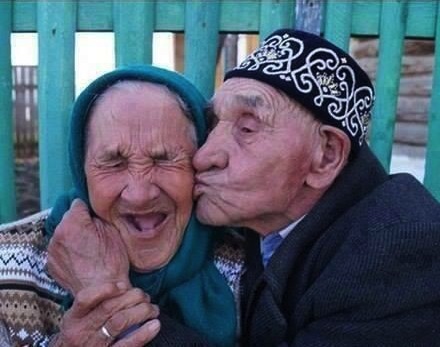

Probably the most significant mentoring happened during my teen years. As a kid growing up the youngest of six brothers and sisters, my parents’ marriage had gone sour by the time I was born and they divorced on my 10th birthday. Although I didn’t realize it at the time, I craved positive family role models and frequently sought invitations from my friends to spend time in their homes, especially with their parents. To this day, those marriages, all of which are still intact, loom large for me when I think of the people who have made the greatest difference in my life.

One of the couples that I adopted was our temple’s youth director and his wife. It’s true that they probably adopted me first, seeing a kid who was stumbling through his teenage years without a whole lot of direction or guidance, and hoped I would use them for some of that. That couple, Rabbi Jon and Susan Stein, were so utterly responsible for the inarguably most important parts of my education – how to work with others, how to lead others, how to become a valued subordinate, how to work with younger children, and how to be part of a successful marriage – that I have no doubt whatsoever my choice to become a rabbi was to try and pay the Steins back for the invaluable mentoring they provided me in my teenage years.

The single most important mentor in my life has been Rabbi Jeffrey Sirkman. He’s also my best friend. I’ve known “Uncle Jeffrey” (as my children always called him) since the very first day of my first year at HUC. We met standing in line to register for classes and have been fast friends ever since. Uncle Jeffrey has shown me more about how to be a rabbi, how to be a husband and a father, and how to be a mentsch, than maybe anyone else on this planet. From the day I met him, I knew I wanted to be near this guy because, like those professors at HUC who stood high above the rest because of their humanity, Jeffrey oozes humanity from every pore. Besides being brilliant, endlessly creative and the best teacher I’ve ever known, he is kind and gentle and respectful and enthusiastic and optimistic. I never cease being awe-struck watching how he interacts with others. Plain and simple, I have tried to be for you what I have seen him be for his congregation.

As Joel and Andy and Ana and Andrew and Susan and Corey and I have all shared this evening, there are individuals whose paths through life intersect with our own, perhaps for many years, perhaps for only a brief time. But because of them, our own lives are forever changed for the better. For being the person they are, and for taking the time to share what they’ve learned with us, the gratitude we feel to these individuals is nearly boundless.

Did it have to be them? Not likely. But because it was them, their names remain forever etched in our hearts. Everything we do, we do a little better because of them.

And now, you and I are challenged to return the favor. As you know, Woodlands – you guys – have supported bringing a rabbinic intern to our congregation, something we had been doing since 1976. It has been important to me to continue this practice because, once upon a time, you permitted me to be your intern and to benefit from the time and guidance of Rabbi Mark Dov Shapiro and so many of you who simply took me in, gave me time to develop some skills, and didn’t skewer me too much when I fell flat on my face. So I’ve been returning that favor pretty much every year since, as well as trying to pay forward the many gifts I’ve received from so many of my teachers and mentors across the years. To you I say thank you, for allowing me to do this. Woodlands is a plum internship, always high on the list of those interviewing for this position. Not because we are leaders and innovators in the American Jewish community, and we are, but because we’re awfully nice people and Woodlands is a wonderful place to come learn about leading and innovating because of that.

Jethro never lorded it over his son-in-law. He never ridiculed Moses or made him feel unqualified to lead. Out of love (okay, and maybe because he wanted this guy to be good husband to his daughter), Jethro was a great mentor.

When Jethro arrived with his daughter and grandchildren to join Moses and the Israelites in the desert, Torah tells us, “He bowed low, kissed him, and asked how he has doing” (Ex 18:8). The Ktav Sofer, a 19th century Hungarian rabbinic commentator, pointed out that the verse is ambiguous. It’s not at all clear who’s bowing, kissing and asking here. That, my friend and mentor Rabbi Larry Hoffman has taught, is where the results of effective mentorship really shine. One no longer knows, or cares for that matter, who’s responsible for praiseworthy actions. Both teacher and student have mastered the skills and have both come to embody the best of what that teacher has had to offer. Moses learned from Jethro not just the professional skills Jethro had to share, but his essential goodness as well.

Eloheinu v’elohei avoteinu v’imoteinu … Your world overflows with opportunity. But it’s a big place, and stumbling abounds. So You hid here for us treasures of immeasurable worth. Mentors. To show us how to get things done. To take us by the hand and lead us, that we might lead others. For the very best of them, You filled their hearts with a goodness that has become their greatest gift. Throughout our lives, may we grow rich in the wisdom and the goodness that these talented and generous people offer. And may we honor You, our Creator, by never turning away from an opportunity to serve in such a role ourselves.

Billy

Of all the stories in the Torah, Noah’s is perhaps the most loved of them all. After all, who can resist the image of all those furry, adorable creatures ascending into the Ark, two by two, and living in harmonious tranquility for the duration of that epic boat ride all those thousands of years ago?

Of all the stories in the Torah, Noah’s is perhaps the most loved of them all. After all, who can resist the image of all those furry, adorable creatures ascending into the Ark, two by two, and living in harmonious tranquility for the duration of that epic boat ride all those thousands of years ago? That would be a funnier joke if so many of us weren’t as concerned as we are about the United States government. With issues like North Korea, Russia, global warming, the treatment of Muslims and the treatment of unauthorized immigrants so prominently and disappointingly in the news, it’s understandable when people express dismay to us about what awaits our nation just up ahead.

That would be a funnier joke if so many of us weren’t as concerned as we are about the United States government. With issues like North Korea, Russia, global warming, the treatment of Muslims and the treatment of unauthorized immigrants so prominently and disappointingly in the news, it’s understandable when people express dismay to us about what awaits our nation just up ahead.

Last weekend, Ellen and I traveled northward to Buffalo where Ellen was officiating at the 2nd wedding ceremony of two very dear men who wanted to marry under the newly-legal auspices of New York State. We joined them on a small boat that travels the famous lock-system of the Erie Canal. Ellen presided over the re-union of the two gentlemen while the boat was being lifted in a lock from one level of the canal to another. It was a beautiful, touching, incredibly loving celebration that, for many of us, was enhanced by the excitement, if not the symbolism, of rising up with the waters beneath us.

Last weekend, Ellen and I traveled northward to Buffalo where Ellen was officiating at the 2nd wedding ceremony of two very dear men who wanted to marry under the newly-legal auspices of New York State. We joined them on a small boat that travels the famous lock-system of the Erie Canal. Ellen presided over the re-union of the two gentlemen while the boat was being lifted in a lock from one level of the canal to another. It was a beautiful, touching, incredibly loving celebration that, for many of us, was enhanced by the excitement, if not the symbolism, of rising up with the waters beneath us. Part of the conversation taking place right now is how the city of Houston could have been so unprepared for the waters of Hurricane Harvey when, back in 2008, Hurricane Ike killed nearly a hundred people and caused $30 billion in damage. It was a dress rehearsal for Hurricane Harvey, and yet little was done in the years since. So while Houston has been experiencing incredible economic growth, it has also erased marshland after marshland, leaving few escape routes for the eventual floods that were coming. They were sitting ducks, they knew it, yet did nothing about it.

Part of the conversation taking place right now is how the city of Houston could have been so unprepared for the waters of Hurricane Harvey when, back in 2008, Hurricane Ike killed nearly a hundred people and caused $30 billion in damage. It was a dress rehearsal for Hurricane Harvey, and yet little was done in the years since. So while Houston has been experiencing incredible economic growth, it has also erased marshland after marshland, leaving few escape routes for the eventual floods that were coming. They were sitting ducks, they knew it, yet did nothing about it.

Eloheinu v’elohei avoteinu v’imoteinu … dear God and God of our ancestors … help us not only to understand that there are different ways to share opposing points of view, but to choose the way that is accompanied by respect and unyielding love. May we understand and acknowledge that those who advocate for that which we’d spend as much energy as we can to oppose, they love this country just as we do. We need not acquiesce but we certainly can listen and (like the rabbi who got the meaning of a song entirely wrong) realize that words spoken to us may feel misguided and hurtful, but these very words are expressing powerful feelings of the speaker’s fear and anxiety concerning what is felt to be an unpromising future for the world they love.

Eloheinu v’elohei avoteinu v’imoteinu … dear God and God of our ancestors … help us not only to understand that there are different ways to share opposing points of view, but to choose the way that is accompanied by respect and unyielding love. May we understand and acknowledge that those who advocate for that which we’d spend as much energy as we can to oppose, they love this country just as we do. We need not acquiesce but we certainly can listen and (like the rabbi who got the meaning of a song entirely wrong) realize that words spoken to us may feel misguided and hurtful, but these very words are expressing powerful feelings of the speaker’s fear and anxiety concerning what is felt to be an unpromising future for the world they love.

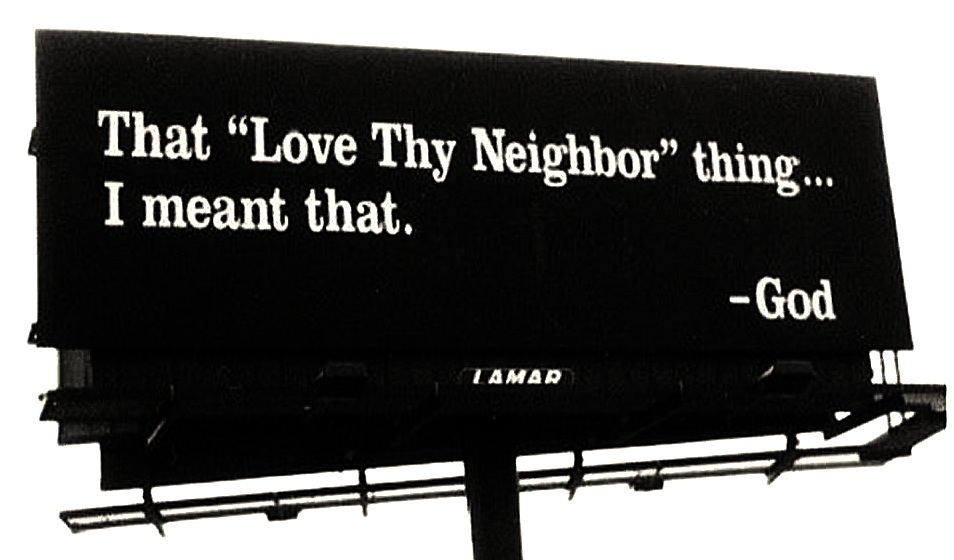

I think of all three of these acts of kindness – two churches that invited us in, and a third church that invited Dylann Roof in – and I pray. May we never close our doors to another human being, especially in their moment of need. May we teach our children that there is no shame in expressing such need, but that it must only be shared through words and tears, never through a clenched fist. May we continue to affirm that God’s love comes into the world through human acts of goodness, so may our spirits be resolute in the faith that it is always right to welcome and to love. And may the day soon arrive when every man, woman and child not only understands, but lives, such faith.

I think of all three of these acts of kindness – two churches that invited us in, and a third church that invited Dylann Roof in – and I pray. May we never close our doors to another human being, especially in their moment of need. May we teach our children that there is no shame in expressing such need, but that it must only be shared through words and tears, never through a clenched fist. May we continue to affirm that God’s love comes into the world through human acts of goodness, so may our spirits be resolute in the faith that it is always right to welcome and to love. And may the day soon arrive when every man, woman and child not only understands, but lives, such faith.

And with that deeply philosophical question which confronts our awareness that something may not be true and yet we cling to the possibility that perhaps it is, Tyler Levan touched upon a debate that has dogged humankind since our brains brought us out of the trees. Religion used to make excellent and effective use of fear to get people to live morally upright lives. The formula was a simple one: do God’s mitzvot and receive God’s reward; stray from God’s mitzvot and prepare to meet thy doom. Such “understanding” of how the world works used to go unquestioned, and many behaved better because of it. Today, we may have great difficulty believing in the doctrine of reward and punishment, but we sure wish it were real.

And with that deeply philosophical question which confronts our awareness that something may not be true and yet we cling to the possibility that perhaps it is, Tyler Levan touched upon a debate that has dogged humankind since our brains brought us out of the trees. Religion used to make excellent and effective use of fear to get people to live morally upright lives. The formula was a simple one: do God’s mitzvot and receive God’s reward; stray from God’s mitzvot and prepare to meet thy doom. Such “understanding” of how the world works used to go unquestioned, and many behaved better because of it. Today, we may have great difficulty believing in the doctrine of reward and punishment, but we sure wish it were real. You may be saying to yourself, “I didn’t know Judaism believes in heaven and hell?” The short answer is yes, we do. What those two things look like, nobody pretends to know. Jewish thinkers and writers throughout the ages have toyed with these concepts, but the rabbis only settle upon this admonition, “Just observe the mitzvot. Be careful how you live your life in this world and the world-to-come will take care of itself.”

You may be saying to yourself, “I didn’t know Judaism believes in heaven and hell?” The short answer is yes, we do. What those two things look like, nobody pretends to know. Jewish thinkers and writers throughout the ages have toyed with these concepts, but the rabbis only settle upon this admonition, “Just observe the mitzvot. Be careful how you live your life in this world and the world-to-come will take care of itself.” It may just be my greatest statement of faith, but I absolutely believe that goodness abounds, that while temptation and perhaps fear can drive us to act contrary to what we know is right, most of us try to do the right thing. And not just because it’s right, but because we like doing good. And I suppose my other great statement of faith is that I believe these things come back to us. They come back in the respect we engender within ourselves. They come back in the admiration and love we receive from others who observe our kindnesses. And maybe they even come back in a loving universe that appreciates the good we’ve done and tries to offer some good in return.

It may just be my greatest statement of faith, but I absolutely believe that goodness abounds, that while temptation and perhaps fear can drive us to act contrary to what we know is right, most of us try to do the right thing. And not just because it’s right, but because we like doing good. And I suppose my other great statement of faith is that I believe these things come back to us. They come back in the respect we engender within ourselves. They come back in the admiration and love we receive from others who observe our kindnesses. And maybe they even come back in a loving universe that appreciates the good we’ve done and tries to offer some good in return.

V’ahavta l’reyakha kamokha … love your neighbor as yourself.

V’ahavta l’reyakha kamokha … love your neighbor as yourself.