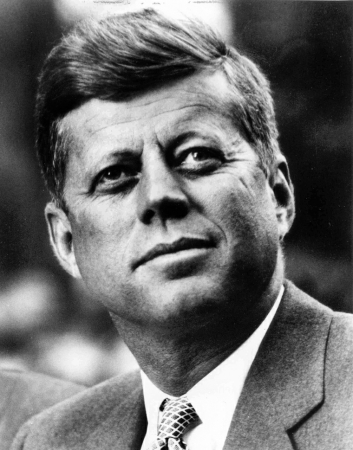

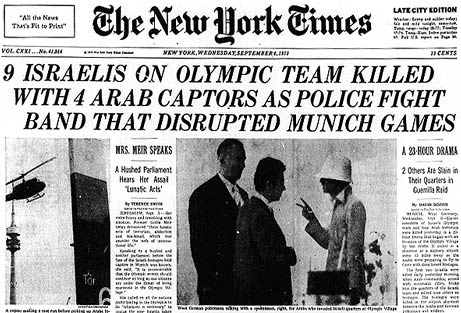

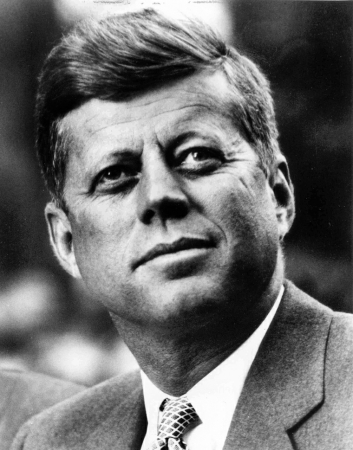

Today marks the 50th anniversary of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. I was six years old at the time of his death and while, unlike many Americans, I do not remember where I was when I learned about it (I imagine I was in school), I do remember sitting in my next door neighbor’s living room and playing on the floor while our families watched the funeral on TV. JFK’s death was a seminal moment in my life as it was for so many others across the world, affecting me (as a kid, at least) far more than any particular Jewish moment had, including the Six-Day War. Which is not to say that the Six-Day War, which took place when I was ten, did not have an impact on me. It did. But JFK’s death meant something more to me as a child growing up in Cincinnati, Ohio, in the sixties.

Today marks the 50th anniversary of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. I was six years old at the time of his death and while, unlike many Americans, I do not remember where I was when I learned about it (I imagine I was in school), I do remember sitting in my next door neighbor’s living room and playing on the floor while our families watched the funeral on TV. JFK’s death was a seminal moment in my life as it was for so many others across the world, affecting me (as a kid, at least) far more than any particular Jewish moment had, including the Six-Day War. Which is not to say that the Six-Day War, which took place when I was ten, did not have an impact on me. It did. But JFK’s death meant something more to me as a child growing up in Cincinnati, Ohio, in the sixties.

This certainly has much to do with my upbringing. My parents were happy to be Jewish. We always belonged to a synagogue. But I would never have described them as “fiercely proud Jews.” Being Jewish was something we were, but not something we were always doing. It would be during my teen years that temple youth group and URJ summer camps would propel me into a more engaged, active involvement in Jewish life.

So with Thanksgivukkah rapidly approaching, something that hasn’t happened for about a hundred years and won’t happen for another (perhaps) 70,000 years, the intersection of American and Jewish life has been on my mind.

Rabbis across the nation have been sounding off on Thanksgivukkah. Some of them view it with suspicion and/or disdain, as if it represents a watering-down of commitment to Jewish life, a cheapening of Jewish tradition. Others welcome it. Probably the same rabbis who, like me, welcome Halloween. In Halloween’s case, some rabbis are put-off by Halloween’s Christian roots, its pagan roots, or its ties to the occult. Others however, including me, dismiss those connections, seeing the holiday as a fun, harmless night of community gathering and socializing. After all, how often do you see your neighbors out on the street? And whatever the holiday’s origins, none of those are why we go trick-or-treating today.

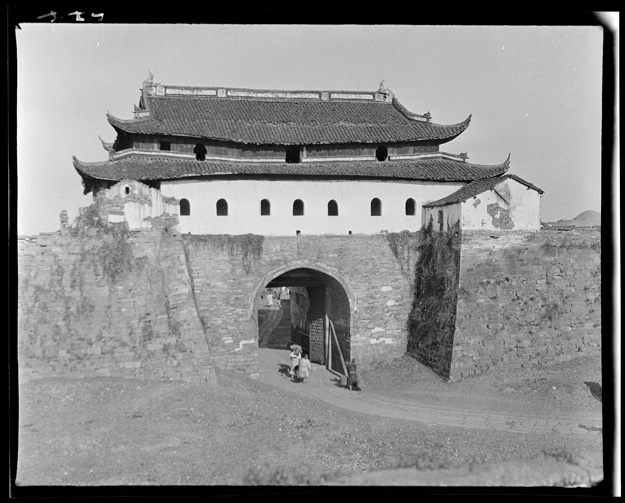

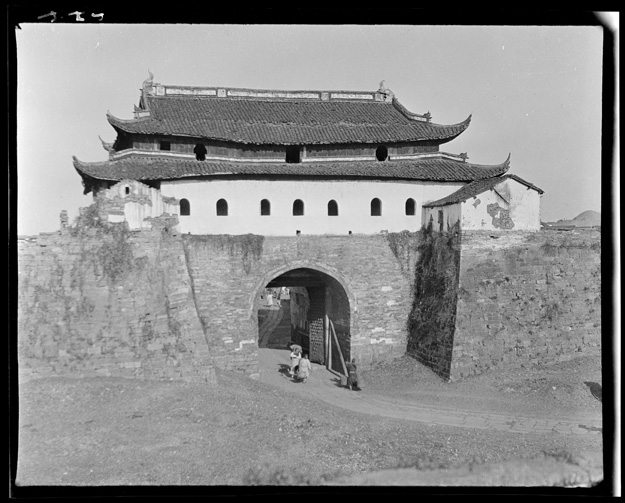

In this week’s parasha, Vayeshev, which will transition us from the Jacob-story to the Joseph-story, the opening words of Genesis 37 highlight for me this challenge of being Jewish and living in America. “Vayeshev Yaakov b’eretz m’gurei aviv b’eretz K’na’an … Jacob settled in the land of Canaan, where his father had sojourned.” The impression we receive here is that while Abraham and Isaac were immigrants, and considered themselves strangers in a new land, Jacob felt at home there. This certainly shouldn’t surprise us. After all, he was a third-generation resident. His grandparents, Abraham and Sarah, had been immigrants. His mother, Rebekkah, was an immigrant. And his father, Isaac, was the child of an immigrant. But Jacob had only known K’na’an as his home.

My grandparents, Philip and Anna Feldman and Harry and Mollie Dreskin, were all immigrants. They took various boat rides across the ocean from Russia to the United States. My parents were the children of immigrants. And I have only known the United States as my home. The children of this congregation, who will be eating turkey and pumpkin pie while lighting candles and opening their Hanukkah presents this year are, in many cases, the great-great-grandchildren of immigrants. They are American through and through.

The commentaries tell us that Jacob became complacent when he settled into life in K’na’an. And everything that befell his children, most especially the travails of his son Joseph and the eventual enslavement of our people in Egypt, were because Jacob had left behind his passion for spiritual living. He’d assimilated. And it led to crisis.

The recent Pew report, “A Portrait of Jewish Americans,” has raised concerns about the impending demise of Jewish life in America. I think the mere existence of a category they label as “Jews of no religion” has the pundits running for cover. Intermarriage, assuming the statistics are accurate, has risen to 58% of American Jews. Between 30 and 50% have little or no connection to the State of Israel. And only 30% think it’s important to be part of a Jewish community.

That’s a lot of people who are gonna miss out on Thanksgivukkah. No menurkey (turkey-shaped menorah) in their homes. No pumpkin latkes. No challah stuffing. And not even their great-great-grandchildren will get the opportunity to celebrate Thanksgivukkah.

Y’all know me. I’m an eternal optimist. Which certainly doesn’t mean I’m right all the time. I just don’t enjoy gloom-and-doom predictions. Yes, I think there are people who are drifting away from, and will ultimately leave, Jewish life. It’s the price of living in America. A free country. Free to go where we want to go, including our spiritual journeys. But that’s only part of the story. The other part I see right here at Woodlands. The 58% that’s intermarrying? A whole lot of them are living wonderful Jewish lives. Not only are they not disappearing from Judaism, but they’re bringing in others! Some are converting, while others are simply joining in. Around here, the results are pretty similar for both: kids growing up who love being Jewish, and don’t doubt for a second who they are even if mom or dad has a second religion.

The fact is, America has been good to the Jews. Its values are consonant with Judaism’s, often originating from the same place! The first Thanksgiving was very likely a reenactment of the biblical Sukkot. As Jews and as Americans, gratitude is an important value. We dine in the sukkah, away from all the creature comforts of the house, to renew our appreciation for the natural world. The first Thanksgiving brought European and Native American together to offer thanks for earth’s bounty. And Hanukkah? It’s also about gratitude. About a world where freedom may be fragile, but it’s worth protecting. And we light candles to celebrate and reaffirm a world where people can live side-by-side, applauding the differences that make life a brilliant tapestry of experience and love.

150 years ago this past Tuesday, President Abraham Lincoln delivered perhaps the most famous oration of all time on a field in Pennsylvania where 8,000 soldiers had lost their lives and another 38,000 were wounded or missing. In his address at Gettysburg, the President enshrined the purpose for which these United States of America had been born: “a new nation conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” He sought to give meaning to the great violence that had occurred there by reaffirming “that this nation under God shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, and for the people shall not perish from the earth.”

Lincoln’s speech, like Dr. Martin Luther King’s speech in Washington, resonate deeply in the Jewish soul. The dream of America, not an easy dream mind you, is a great dream, a dream worthy of our prophets! Isaiah and Jeremiah would, I think, have approved. They’d be disappointed in our setbacks, our failures, our lack of follow-through, but they’d rail against anyone who suggested the dreams were not good ones.

And that’s why I celebrate Halloween. Imagine, living in a country where children can go door-to-door, begging for food they don’t need, and getting a piece of candy and a smile to send them on their way. I know, there are far too many ghettos and rural backroads where good food is in short supply and no one would allow a child on the streets at night. But Halloween encompasses the dream … that one day, all of our children will be able to dress up like monsters and won’t have to ever face real ones.

And that’s why I’ll be celebrating Thanksgivukkah. Because America is about as Jewish a country as you can find (without it being Israel). And Judaism is about as American a religion as you can find, until (of course) you meet your Christian, Muslim, Hindu, Sikh neighbor who also values freedom, full bellies, and peaceful streets.

When JFK got shot in 1963, even as a six-year old I knew something terrible had happened in America. And even as the history books are revising their esteem for the country’s 35th president, John F. Kennedy symbolized every hope and ideal millions of this nation’s citizens held close. Our shared dream of a land that all men and women could call home was sharply muted by the crack of Lee Harvey Oswald’s rifle. Our innocence stolen away, we have been forced ever since to see all of America, its glories and its horrors, and to work to build a future that is forever at risk, to struggle to continue to believe in a better day.

But then, that’s the Jewish dream, isn’t it? Bayom hahu yih’yeh Adonai ekhad ush’mo ekhad … on that day, God shall be One and God’s name shall be One. Which day? The day when we finally bring all people together, regardless of skin color, religious identity, even political beliefs, and join hands to finally, at long last, build a world of peace.

When Jacob settled in K’na’an, he may have given up his years of wandering, but he brought up at least one child who possessed an exalted vision of life as it could be. And in time, it would be Levi, one of Jacob’s wayward children, who would become the ancestor of perhaps our people’s greatest leader, Moses. Jacob may have settled down, and he may have settled for something less than his grandfather had hoped for, but he did not settle for a life devoid of meaning or vision.

And neither have we.

America need not be the dilution of anything. It stands for so much that is good in our world. It serves as the petri dish in which Jewish life can grow and thrive and prosper and, most importantly, do the good that was commanded of us by God at Mount Sinai … the same good by which this nation’s founders hoped the American people would live.

Happy Thanksgivukkah. As an American and as a Jew, I am so grateful for the life that is mine and for the possibilities of goodness for others that, although elusive, are very much worth all of us, together, striving for.