Zero to Hero

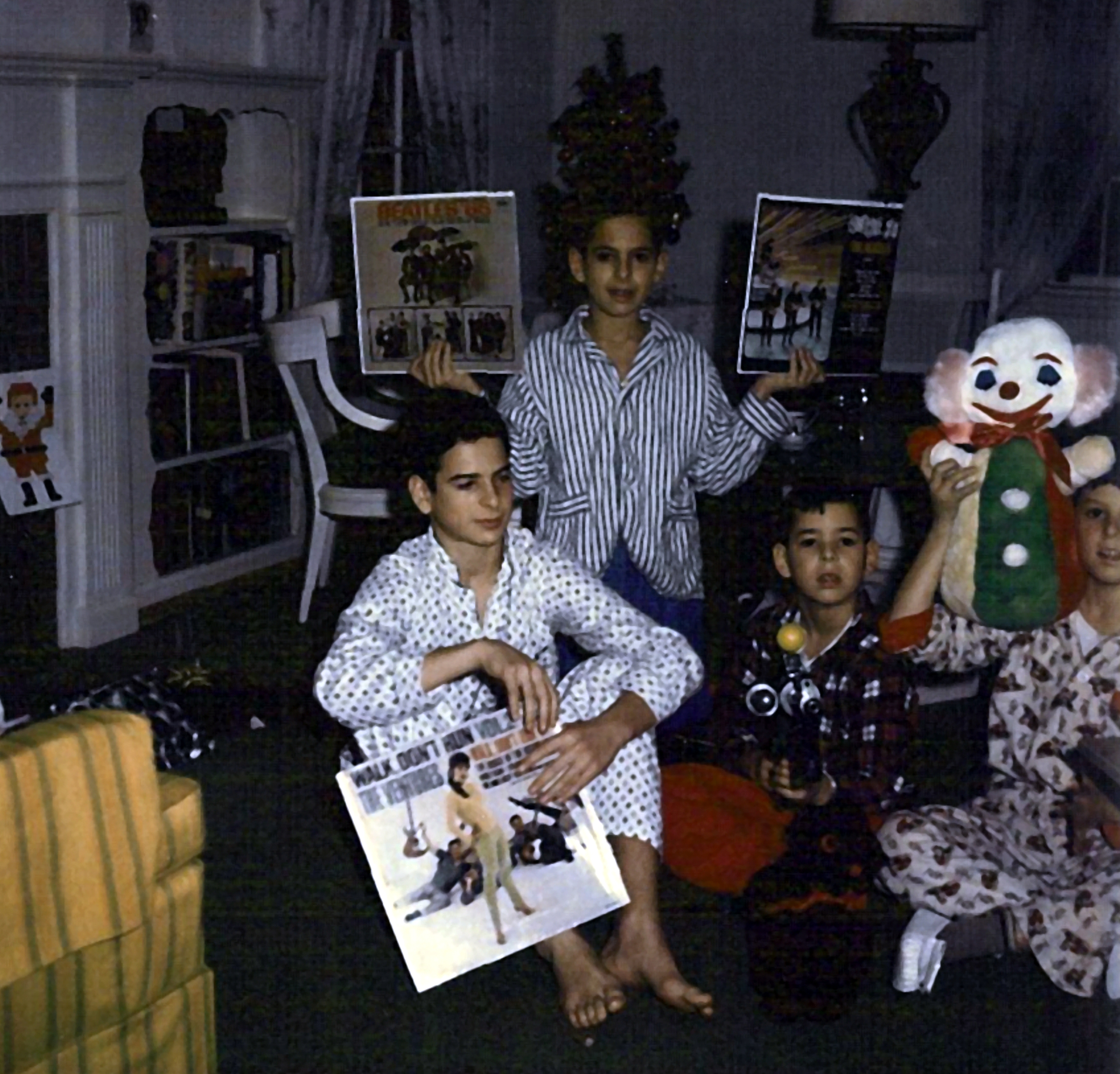

My brother Jimmy came up from Florida last week to spend time with me and my family. Jimmy is number five of the six Dreskin children. I’m number six. We’re two years apart. Much of my childhood was spent fending off attacks – both physical and psychological – from Jimmy. When I was six, he sent me flying through our all-glass front door bestowing upon me a wrist-to-elbow scar that has been ever-so-useful, to this day, in prompting his guilt-ridden conscience to do pretty much anything I ask of him.

So, for seven days this past week, Jimmy fixed things around my house. And since he used to build houses for a living, he can pretty much fix anything.

But here’s the problem. He fixed things a little too well. Our bathroom door, which used to require powerful effort to move it along the carpet in order to open or close, is now damaging my dresser when I push it too hard and it flies above the carpet only to be stopped by what used to be the beautiful finish of our bedroom furniture. Same with the bathroom mirror. It used to not even close but now, held firmly in place by a strong magnet, my pull to open it sends it careening into the adjacent wall. And then there’s the secret annex, a collection of shelves that is home to many family photographs but whose existence hides a storage space behind which we keep our Shabbat paraphernalia, cookbooks and more. The shelves used to require a rather Herculean effort to lift and simultaneously pull the unit open. Now, thanks to my brother, a simple, gentle tug will access its interior. But since my brain’s neuron-firings haven’t yet learned that, I continue to lift and pull which sends the photographs flying across the room.

I say this all not to complain about my brother. Although that’s always fun. To the contrary, I am in awe of his abilities. And after helplessly standing by as, year after year, more parts of our home whither and atrophy, Jimmy’s prowess at restoring hinges and catches and the like makes him nothing less … than my hero. Ellen’s delight at walking into our kitchen and having a flood of light replace the dim shadows she’s cooked in for two decades is all the reward this husband ever needs.

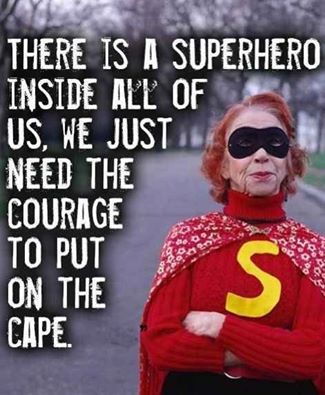

Which got me thinking about heroes.

We all grow up, I think, with pretty clear ideas of what makes a hero. Heroes save lives. Heroes sometimes sacrifice their own to do that. They certainly put their own welfare last when it comes to helping others. War heroes like Gen. George Washington in the Revolutionary War, Maj. Eddie Rickenbacker in World War I, and Lt. John F. Kennedy in World War II, conjure up magnificent images of brave men risking it all to save others. When 9/11 occurred, firefighters and police officers became our heroes as we watched them run into falling buildings to rescue those trying to get out.

We all grow up, I think, with pretty clear ideas of what makes a hero. Heroes save lives. Heroes sometimes sacrifice their own to do that. They certainly put their own welfare last when it comes to helping others. War heroes like Gen. George Washington in the Revolutionary War, Maj. Eddie Rickenbacker in World War I, and Lt. John F. Kennedy in World War II, conjure up magnificent images of brave men risking it all to save others. When 9/11 occurred, firefighters and police officers became our heroes as we watched them run into falling buildings to rescue those trying to get out.

Recently, we have seen heroes work their magic in ending the Ebola outbreak in Africa, aiding victims of the earthquake in Nepal, and fighting the flames of major fires out west. These folks do the work that needs to be done if lives are to be protected, but is work that neither you nor I can nor (probably) would want to do.

Jewish tradition has its heroes too. Noah saved the remnants of global destruction. Abraham risked the wrath of God to challenge the Divine’s decree against Sodom and Gomorrah. Esther knew her place but stepped away from it in order to reverse a king’s edict for genocide. Young David felled the mighty Goliath. And the prophetess Deborah led successful military campaigns against Israel’s enemies, freeing Israel from oppression beneath the yoke of Yavin, king of Canaan.

Tzedek, tzedek tirdof, the Torah teaches us. “Justice, justice you shall pursue.” Paving the way for myriad heroes to arise from our own ranks effecting social change for the better in all corridors of human life.

And so we’ve seen Jews step up and be counted in so many different heroic ways. In 1964, Andrew Goodman gave his life in the struggle for civil rights. In 1952, Dr. Jonas Salk developed the first successful polio vaccine. In 1776, Polish-born American-Jewish businessman Haym Solomon was possibly the prime financier of America’s involvement in the Revolutionary War. In the early 1900s, Julius Rosenwald, co-owner of Sears and Roebuck Company, established a fund that helped build nearly 5000 public schools for America’s black children. Film director, producer and screenwriter Steven Spielberg not only brought us “Schindler’s List,” but, in 1994, created the USC Shoah Foundation Institute which has recorded and preserve testimony from nearly 52,000 Holocaust survivors and other witnesses.

The list goes on and on. And on. And on. And on. Our measly 1/4 of 1% of the world’s population has effected immeasurable change for the better throughout the world.

Had to wander back through time a bit to get all the Dreskin men (and then some) in one photo (my wedding, 1982!)

And then there’s you and me. During his week with us, Jimmy was telling me how he’d done nothing of importance with his life. It’s a Dreskin trait, especially among the Dreskin men. My father, a much-loved physician in Cincinnati, always lamented that he’d not won a Nobel Prize in medicine. As a kid, Jimmy had dreamed of becoming a nuclear physicist. While he had the brains for it, he lacked the ability to sit still and do the hard studying to get there. And me? I look at rabbis like Gordon Tucker in White Plains, David Wolpe in Los Angeles, and Rick Jacobs at the URJ, and, like my father, I too lament what I have not become.

Do you suppose I was listening when I said to my brother, “Are you kidding me? Look at your life. Look at the beautiful, loving, giving children you’ve brought into this world. Look at the home you’ve built for them, a space in which they grow, safe and loved. And look at the good you’ve done for so many by making their electricity work, their roofs not leak, their doors and windows open and close, and a thousand other ways that you improve other people’s lives. Believe you me, when you get the lights working or fix the heat in one of the homes you’ve visited, you’re that family’s hero.”

Maybe I’m stretching the definition a bit. I don’t know if we have to risk limb and life in order for others to place us in that superlative category. Sometimes a quiet conversation when someone is troubled can leave that person feeling like their life has just been saved. Even a student who’s got a paper on ancient Greece due in three days and, not knowing how to get the work done, is calmly ushered through by a teacher or a mentor who simply takes the time to help – that’s a hero.

My wife Ellen’s mom is 93 years old. She’s blind and suffers from dementia. Other than that, she’s been nearly as healthy as a horse. But this summer, her body put her through the wringer and it didn’t look like she’d be around much longer. Ellen and her sister Claudia tended to their mom around the clock, sometimes trying to save her life, sometimes just trying to make what appeared to be the end a bit more comfortable. It was exhausting work for them. To me, it was heroic. What a gift, whatever the outcome, that they gave to their mom. A gift of profound love during this late chapter of her life.

Even when the photographs of Pluto began streaming back to earth from three billion miles away this summer, I very proudly made one of them the feature image on my phone, so grateful was I that some team of rocket scientists and computer geeks had figured out how to show us a piece of creation that resides so far away.

I’m pretty enamored of heroes. And I try to stay open to every possibility for meeting new ones.

Hanging in my home is a framed piece by artist Brian Andreas who draws somewhat goofy but delightful cartoons accompanied by pithy words. This one reads: “Most people don’t know that there are angels whose only job is to make sure you don’t get too comfortable and fall asleep and miss your life.” Ellen, one of the wisest people I know, put the Andreas piece on our wall. It reminds us both that the world is an amazing place and that there are equally amazing people living in it. We ought never get so busy nor so preoccupied with ourselves that we can’t find time to be amazed. Hence, the Pluto pictures on my phone.

Kohelet wrote, Ein kol hadash takhat hashamesh … there’s nothing new under the sun. While many read this verse as an excuse to be blase about everything because, after all, we’ve seen it before, Kohelet’s point was quite likely the opposite. Stay awake. Stay alert. The world never stops being amazing. And if you think it has, you’re missing out on the best life has to offer.

To see as heroic the sandwiches a young parent makes for a kindergartner’s first day of school … makes the world a bright, interesting, affirming and wonderful place. To see as heroic the young idealist who licks envelopes so that others can receive and learn about the candidate this kid thinks will be great for our community … warms our hearts and fills us with hope that a new generation is going to do what they can. And yes, to see as heroic the efforts of a big brother who once scarred his bratty kid brother for life and now fixes his doors and cabinets so that they move freely for the first time in years … why not?

To love and appreciate because someone can – you fill in the blank – administer a life-saving drug, cook a nourishing meal, teach a curious child, give a warm, loving embrace, are these not among life’s most spectacular moments? And are these people – you, me, the members of our families, our friends, our neighbors – not performing heroic deeds by simply showing up to life each and every day, doing the same, un-famous things year in and year out, and being loved for it as if we were world-acclaimed celebrities?

To love and appreciate because someone can – you fill in the blank – administer a life-saving drug, cook a nourishing meal, teach a curious child, give a warm, loving embrace, are these not among life’s most spectacular moments? And are these people – you, me, the members of our families, our friends, our neighbors – not performing heroic deeds by simply showing up to life each and every day, doing the same, un-famous things year in and year out, and being loved for it as if we were world-acclaimed celebrities?

My teacher, Rabbi Larry Hoffman, writes about wrinkles and how they are the marks of a life that’s been lived. It’s up to you and me to decide whether it’s been well-lived. But we get credit – lots of credit – for just showing up. True Dreskin that I am, I lament the accomplishments that I haven’t achieved. But then I look at you, at this beautiful, sweet, holy community, and I thank my lucky stars that you believe I have enough to offer that you invited me and my family to move in with you twenty years ago.

Ein kol hadash takhat hashamesh … there’s nothing new under the sun. But we can, and ought to, renew how we look at everything under the sun. It may not be new. But our appreciation of it might be.

I really am in awe of my brother’s abilities to improve the space that a person lives in, to make it lovelier and more functional. Can a million other people do the very same thing? Absolutely. But for the folks who creak front doors he is invited to walk through, Jimmy is the most important of them all.

Someone else will treat the illnesses. Someone else will put out the fires. But for those who are lucky enough to have you and me step into their lives and make a sandwich, explain something confusing, give a hug, even fix a broken light switch – we too can be their heroes.

Let’s just be sure we don’t get too comfortable, fall asleep, and miss out on the excitement.

In 2012, astrophysicist Summer Ash underwent heart surgery to replace a defective aorta. Upon her recovery, Summer discovered that her heart had developed certain acoustic anomalies that resulted in her heartbeat becoming audible to the naked ear. She, and others sitting close to her, could hear the steady beating from inside her chest, not through a stethoscope but from the heart itself.

Through this odd experience, Summer Ash achieved a level of recognition of her heart’s purpose. With her engineer’s brain, she understood the heart as a pump. But as a human being with this unique experience of living with her own audible heartbeat, always, she came to appreciate the work our hearts do to keep us alive, every minute, every day.

A different kind of hero, to be sure. But with the same message, I think … to not miss out on our lives, and to give thanks for the great gifts that are bestowed upon us … every minute, every day.

Billy