Elul: Preparing to Forgive … Others, and Ourselves

The 19th century German poet and essayist Heinrich Heine once wrote, “All I ask is [for] a simple cottage, a decent bed, good food, some flowers in front of my window and a few trees beside my door. Then if God wanted to make me wholly happy, He would let me enjoy the spectacle of six or seven of my enemies dangling from those trees. I would forgive them all wrongs they have done me – forgive them from the bottom of my heart, for we must forgive our enemies. But not until they are hanged!” (as quoted in Edge-Tools of Speech,1899, Maturin Ballou, p. 169)

‘Tis the season. In a little more than a week, we’ll enter our tent, open our makhzorim, and begin our annual period of reflection and contrition, with the goal of teshuvah, of recalibrating our hearts that we might become more compassionate – to others and to ourselves – in the New Year ahead.

‘Tis the season. In a little more than a week, we’ll enter our tent, open our makhzorim, and begin our annual period of reflection and contrition, with the goal of teshuvah, of recalibrating our hearts that we might become more compassionate – to others and to ourselves – in the New Year ahead.

I’m not at all clear how these High Holy Days actually affect us. I do, every now and then, encounter someone who, prior to the arrival of Rosh Hashanah, offers me an apology for anything he might have said or done that hurt or offended me. But I’m not impressed by that. I don’t think that’s teshuvah at all. There’s no turning, no recalibrating, going on because there’s no knowledge of having done anything wrong. “If I’ve done something, I’m sorry”? Better to find one person we know we’ve been unkind to and put our New Year’s energy into fixing that one relationship. It takes courage to confront someone we’ve wronged, to apologize when we know we’ve behaved poorly. To issue some blanket memo to try and cover our bases neither warms the heart of the person we have wronged, nor teaches us any lesson about ourselves … except maybe that we don’t care enough to really figure out where we’ve fallen short.

The upcoming Y’mei Aseret Teshuvah, the Ten Days of Turning from Rosh Hashanah through Yom Kippur, are not meant to be easy. But for most of us, that’s pretty much what they are. Our greatest challenge is to make it through the fast on Yom Kippur. I’m not sure that many of us really do the difficult soul-searching that’s demanded by the texts in our makhzor. I’m not sure we do the real forgiving that these High Holy Days challenge us to do.

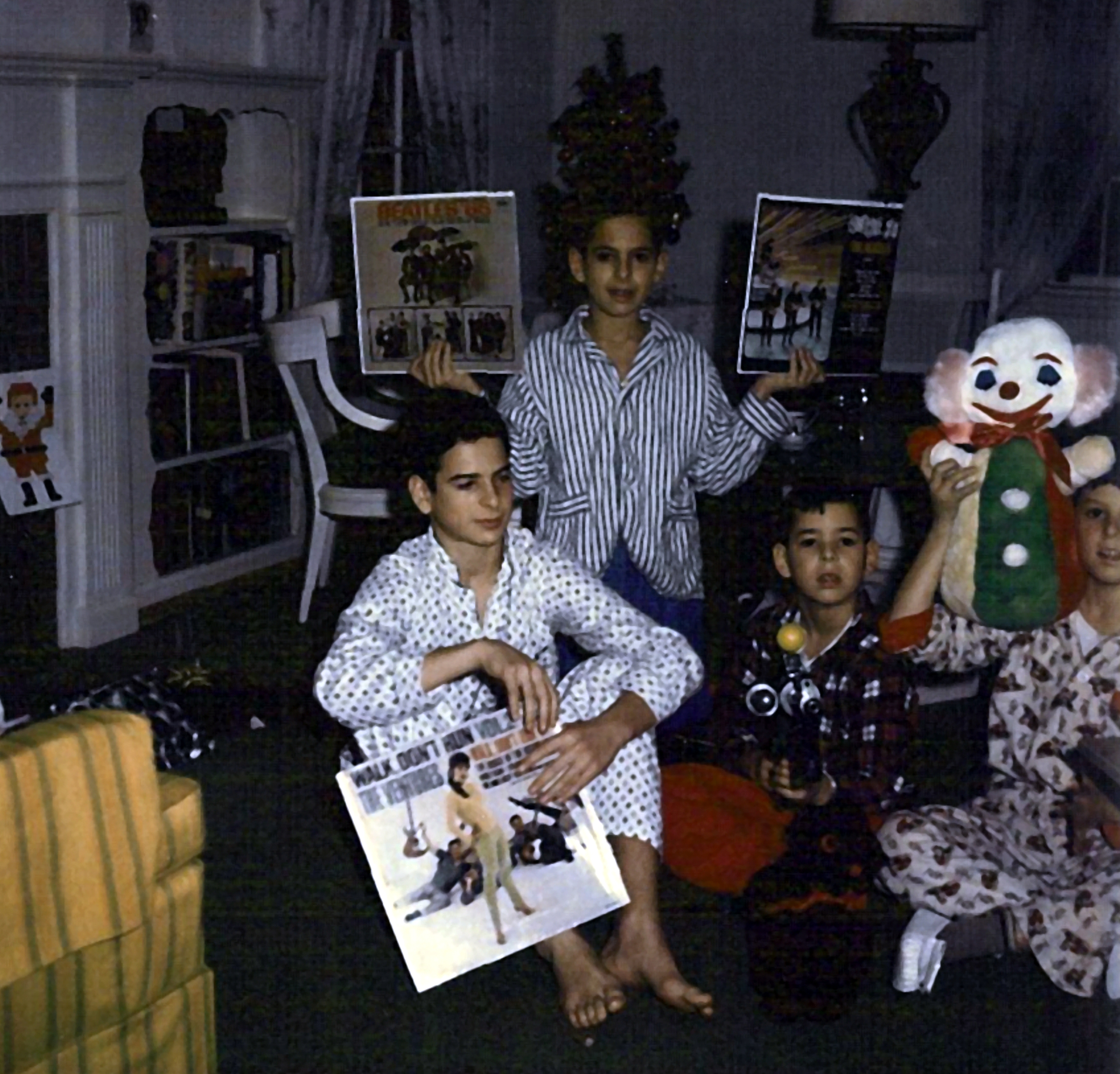

A few weeks ago, I spoke about my brother Jimmy and how he’s my hero. I joked about the scar he’d given me when I was six and he was eight and he’d chased me through our house threatening to smash a wet noodle in my hair and I ended up crashing through the plate glass of our front door. When, some fifty years later, I learned that he still feels guilty about that, I shared with you how I take full advantage of his guilt which, most recently, resulted in his coming up from Florida and repairing just about every broken hinge, light and damaged wall in my home.

The reality … is that I forgave him a long time ago. But that was easy. He’s my big brother. And I worship him. And adore him. I could never hold a grudge against him.

Unfortunately, it gets easier where others are concerned.

Rabbi Nakhman of Bratslav, the late-18th century founder of the Bratslav hasidic community in the Ukraine, noticed how people hold grudges, how our anger can cause us to push someone completely away and out of our lives without any interest in repairing the rift but, instead, concluding there is nothing redeeming in that person and there is no value in trying to make amends.

To try and counter such behavior, Reb Nakhman wrote: “[For] even someone who is completely wicked, one must search and find in him some little bit of goodness, because within that one little part of him, there is no wickedness.”

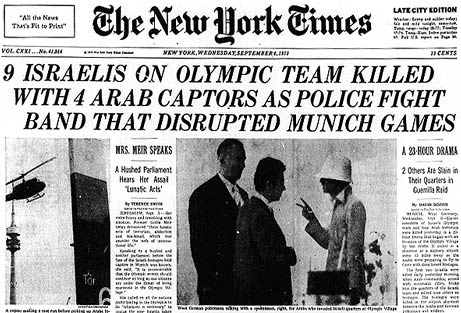

When I first read this, I was thinking of truly evil people like Caligula or Hitler. With the likes of such mad men, it’s easy to write them off as monsters. It hadn’t occurred to me that, when we’re angry at someone who’s not a Hitler, we can paint that person as if they are completely awful, possessing no redemptive features whatsoever. In our saner, more sanguine, moments, we understand we’re not talking about Caligula; it’s just that idiot Bob from work, or my dumb neighbor, or my sibling with whom I haven’t spoken in fifteen years.

Reb Nakhman urges that we: “find in him a little bit of good, judge him on the side of merit, and in this way, raise him up and enable him to turn in teshuvah.”

I may be reading this wrong. But the teshuvah here, the turning, I don’t think it’s Bob’s. It’s ours. Yours and mine. When we’re furious at someone, we need to find a tiny crack in the armor we’ve built around that other person – armor that shows (and defends) only what we hate about them. Reb Nakhman teaches that we need to see the whole person, not just the parts we resent. We need to come to understand that, despite our brilliantly deduced conclusions, people are salvageable.

Unlike my attitude toward drivers who don’t use their turn signal, and I wish horrible things upon them because of the danger they create by not letting other drivers know their intentions and therefore reduce our ability to react safely to an unsafe moment on the road. At those moments, it could be Malala Yousafai and I wouldn’t be able to see a single redemptive quality in her.

Unlike my attitude toward drivers who don’t use their turn signal, and I wish horrible things upon them because of the danger they create by not letting other drivers know their intentions and therefore reduce our ability to react safely to an unsafe moment on the road. At those moments, it could be Malala Yousafai and I wouldn’t be able to see a single redemptive quality in her.

Reb Nakhman says about the one we resent, that we should ask ourselves: “How is it possible that she never fulfilled a single mitzvah or good deed in all her days?” Reb Nakhman teaches that when we push ourselves to look for the goodness that resides somewhere inside each one of us – even my annoying neighbor who blows his leaves at 6:30 on a weekend morning – when we succeed in finding those redeeming qualities, then redemption can begin. Our redemption.

Despite my behavior behind the wheel, sometimes I’m amazed at my capacity to forgive. My brain continues to argue with me, “Are you kidding?” it shouts. “You’re going to let them off the hook for what they did to you!?”

And my answer is: Yes. I am. Because life is a whole lot bigger than stupid, annoying, hurtful moments. I’ve got better things to do with my time. Life is far too short to spend it pursuing resentment and rejection.

Shlomo Carlebach, who’d fled the Nazis as a young man, was once asked how he could go back to Austria and Germany to perform. “Don’t you hate them?” he was asked. Carlebach responded, “If I had two souls, I’d devote one to hating them. But since I have only one, I don’t want to waste it on hating.”

Rabbi Rami Shapiro challenges us to view Rosh Hashanah as “head-changing day.” He derives this from “head” (rosh), and “changing” (shay-nah, a variation on HaShanah).

“You can’t have a new year with an old head,” he writes. “So if you want a new year, you are going to need to get a new head. A new head is a story-free head. Your stories define you. If your stories are positive and loving, then you are [positive] and loving. If your stories are negative and fearful, then you are [negative and fearful].”

Rabbi Shapiro encourages us to rewrite our stories. To focus on truth. And to focus on compassion. To cast away the stories that frustrate us, that anger us, that make us turn away from others.

It is the 21st day of Elul. Soon we will gather for our Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur heshbon nefesh, our annual soul-searching. May the year 5776 be the one in which we truly master the art of teshuvah. May we turn our spirits toward You, God, by turning them away from bitterness, resentment and hatred. May these Ten Days of Turning bring real change. To our heads, to our hearts, to our spirits. And may we share together in a New Year that is filled to overflowing with kindness, tolerance, understanding, radical inclusion, and love.

Billy