Thank You! (Final Sermon @ WCT, Jun 25, 2021)

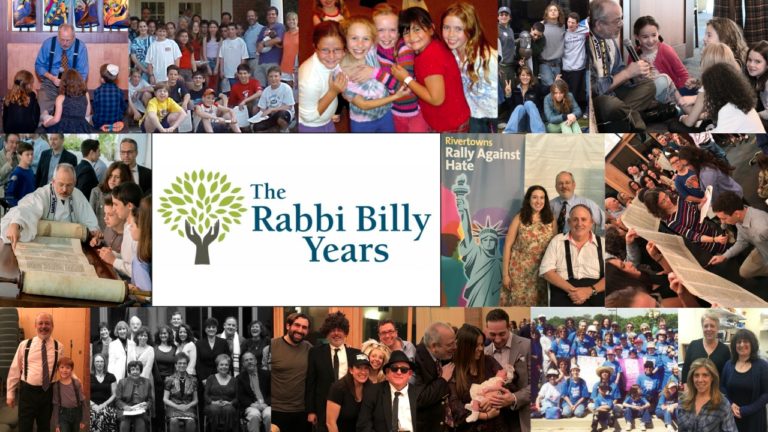

This past Friday, I said goodbye to my congregation of twenty-six years. It’s been a wonderful adventure. These are my words before departing.

This past Friday, I said goodbye to my congregation of twenty-six years. It’s been a wonderful adventure. These are my words before departing.

* * *

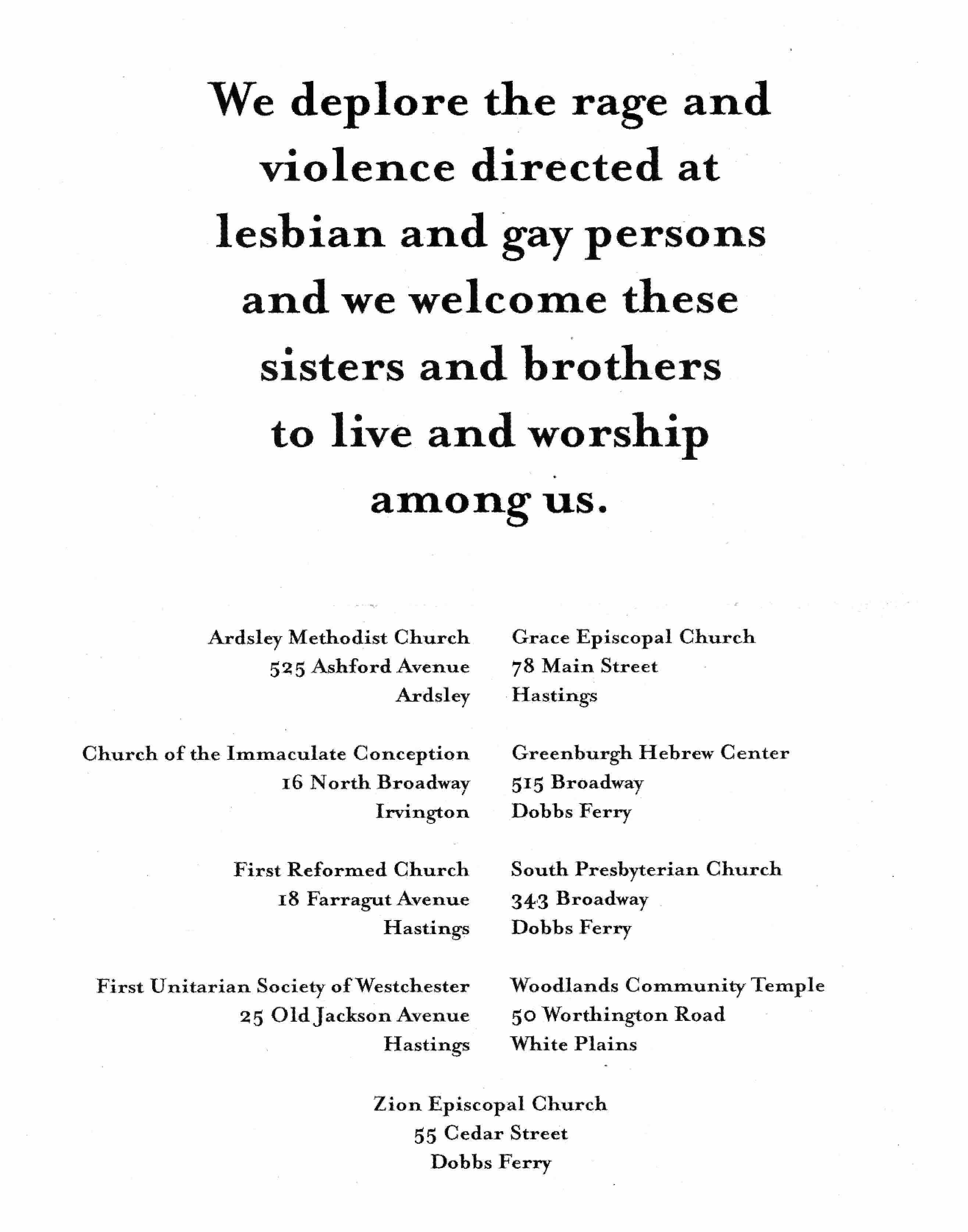

In 1986, when I was Woodlands’ rabbinic intern, Rabbi Mark Dov Shapiro invited me to explore whether or not temple members might like to participate in Hands Across America, whose goal was to bring millions of us together in an unprecedented attempt to form a continuous human chain across the country.

While the chain wasn’t quite complete, participants did raise about $15 million to feed and shelter America’s families in need. Back here at Woodlands, we filled three school buses which were supposed to drop us onto the George Washington Bridge. We only managed to get as far as the ramp leading up to the bridge, but it was still pretty exciting. If I hadn’t yet fallen in love with this temple, I certainly had by the end of that day.

Pretty much every intern who’s ever been lucky enough to spend time at Woodlands has dreamed of coming back as its rabbi. When I actually succeeded in doing that back in 1995, I received messages from many past interns letting me know that I was carrying all of their dreams with me.

That’s the effect that your synagogue has on people. There’s a reason Cantor Jonathan was here for 22 years. There’s a reason I’ve been here for 26 years. And there’s a reason that Rabbi Mara’s internship just kept morphing into new roles for her. We all stayed because we love this place.

At one time or another, you’ve probably heard mention of “The Woodlands Way.” It’s the special sauce that makes so many of us cherish this place. And while there’s absolutely no agreement as to what that “sauce” is, it leads us all to the same conclusion: Woodlands Community Temple … makom shelibi oheyv … it’s the place that our hearts hold dear.

When I was attending rabbinical school, I had two dreams about the congregations I would serve. First is the one we all had, let it be a place we like — which isn’t as easy to find as you might think. And God knows, some of you have given me quite a few challenges through the years but, on balance, Woodlands is just about as easy-going as a synagogue could possibly be. There are, of course, wisdoms for clergy to acquire that has made living with y’all possible. But once those had been learned – and admittedly, it took me far longer to do so than it did either Cantor Jonathan or Rabbi Mara – Woodlands became what constituted my second dream while in rabbinical school: to stay in one congregation for a generation.

And that’s what I’ve done — what you’ve allowed me to do. I’ve blessed your babies, blessed your Consecrants, blessed your B’nai Mitzvah, your Confirmands, your Graduates, and blessed your brides and grooms. I’ve sat with you in hospitals and stood with you in cemeteries. We’ve learned together, celebrated together, cried together, and worked to change the world together.

That’s what it means to stay in one congregation for a generation. And I am so lucky to have done that, and to have done that here at Woodlands.

I’ve had many favorite moments across the years, and I couldn’t possibly list them all. But here are just a few of them.

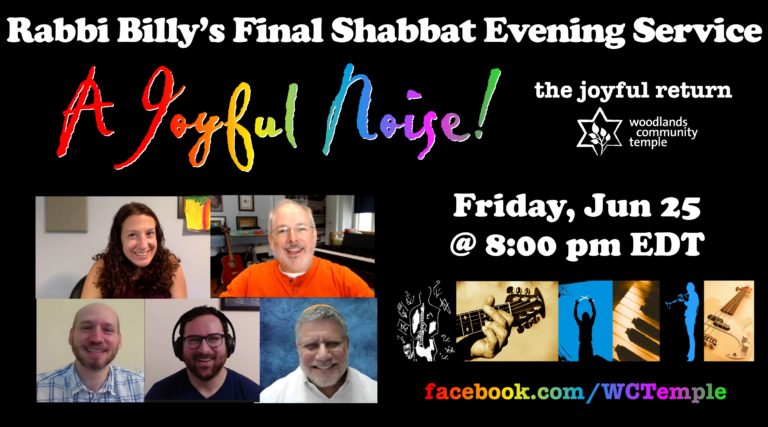

The Million Mom March in 2000, the March for Women’s Lives in 2004, and the Darfur Rally in 2006, all in DC. Our very first visual t’filah in 2006. Traveling to Ocean Springs, Mississippi, in 2007 to help with Katrina Relief, and the fact that the project continued annually for ten years. Israel trips. Tent Sales. Hevra Torah. Talmud Study. The Christmas Eve Midnight Run. Thanksgiving Morning cooking (and how it always took me most of the morning to get the Macy’s Parade onscreen for us). Exotic Shabbat, nine Friday nights between 1996 and 2003 that we dedicated to laughter. Seventh Grade Family Torah. The night in 2002 when we said goodbye to the old sanctuary. Moving the temple offices into Elmsford while the temple was being renovated in 2002, and a prospective wedding couple asking me if I could prove I was really a rabbi. Everything interfaith: from shared learning to shared grieving, responding to Charlottesville with the Rivertowns Rally Against Hate, an interdenominational babynaming during the Friday night after the Tree of Life shooting. sTorahtelling. Hanukkah 2006 when WoodSY hijacked our Shabbat service to replace the Ner Tamid with a more energy-efficient bulb. The arrival of A Joyful Noise in 2007. Yoga Shabbat. Nashir, a national teen songleading program that landed several times here at Woodlands. Sharing with you the incredible story of the Yanov Torah, and your overwhelming response that resulted in bringing the Azizi family to America from Afghanistan. The fun we had when Shavuot fell on Memorial Day weekend and we replaced services and learning with “The Sinai Challenges” on the front lawn. Texting Shabbat in 2017 when we forced you to use your phones during services! Placing the “All are Welcome Here” sign on our front lawn when the Trump administration began slamming gates everywhere else. Mitzvah Hero Training before Jammin’ Shabbat. After Super Storm Sandy in 2012, Mara and I opening the Ark for Alenu only to find it empty because we’d forgotten to return the scrolls from safe storage. Michael Ochs and Alaa Alshaham, a Jew and a Palestinian on our bimah for Shabbat in 2014, and hearing Jewish prayers sung, for the very first time in our lives, in Arabic. Then there was everything we did for each during the pandemic. And of course, everything you did for me and my family when Jonah died, including the Jonah Maccabee Concert which not only brings great Jewish music to Woodlands and raises much-needed funds to help kids get to URJ summer programs, but ensures that Jonah’s memory lives on.

While those may be some of my favorite moments, they’re still just the tip of the iceberg. In twenty-six years, there have been tons of holidays, High Holy Days, Shabbat services, adult ed classes, Confirmation classes, stories at religious school t’filah, committee meetings, family meetings, pastoral meetings, and the list goes on and on and on. Which I mention not at all to brag, but to thank. A job like this has never been doable by one person. The support that I have had every step of the way has been invaluable and crucial. And so, here are a few thank yous that must get said.

First, my family. First and last and everywhere in between – my sweet, loving, precious family. No one has given more to this temple than you. The number of times I have had to leave you, the number of times I haven’t come home, the number of times you’ve taken a back seat so I could take care of someone else, and the number of times you have supported me when things got a mite heavy around here. I owe you everything. And for that I give you my thanks, my love, and this promise: From here on out, it all gets dropped for you.

For perhaps the first time in twenty-six years, you all take a backseat to them. But only a backseat. Because I owe you all so much too, for helping me succeed, helping me grow, helping me take care of you, helping me help you to build vibrant Jewish life at Woodlands.

And so I thank my temple presidents: Lois Green, Maxine Howard, Lance Rosenthal, David Fligel, Chuck Fishman, Rochelle Stolzenberg, Stu Berlowitz, Dayle Fligel and Andy Farber. Only your Boards know how much work you do around here. It’s unbelievable what you do. And I am grateful for every bit of it.

I thank my temple Boards. You have partnered with me to ensure Woodlands has stayed strong, weathered the bad, and built a spiritual home for thousands upon thousands through the years.

I thank everyone who’s ever worked in the office, from Renee Doynow and Marilyn Alper to, most recently, Liz Rauchwerger, Marjorie Mattel and Michelle Montague. All of you have kept this place on an even keel, making sure every staffperson and clergyperson has what they need, making sure every volunteer has what they need, and making sure every congregant is cared for in their moment of need.

I thank the three men who have cared for our building in the years that I’ve been here: Dominick DeFabritis, German Franco and Hernando Carmona.

I thank my Joyful Noise family. You guys have been so much fun. And you’ve let me push you around; I think you’re the only ones at Woodlands who’ve let me do that. Thank you for making music with me. And thank you for sticking with me … for fourteen years! What a treat and a delight you have been.

I thank my cantors: Cantor Julie Yugend-Green, Cantor Jonathan Gordon and Cantor Lance Rhodes. And Cantor Ellen Dreskin. Because she’s a cantor. Because she actually was my cantor during my interim year. And because, well, she’s my wife – and nothing beats that!

I thank my Directors of Cong’l Learning: Cantor Ellen Dreskin (yep, that interim year), Harriet Levine and Rabbi Mara Young. An army may march on its stomach, but a synagogue? On its kids. The care you have given them, the learning you have provided them, and the calm reassurance with which you have swaddled their parents – you are a mighty army of your own. Your deeds have been feats of magic, and our congregation owes you so much. As do I.

I thank my Directors of Youth Engagement: Scott Newman, Ross Glinkenhouse, Tara Levine and Lily Mandell. Just the other day, I was speaking with Rabbi Jonathan Stein, who had been my youth group advisor when I was in high school, telling him that one of the strongest, most persistent reasons I became a rabbi was to pay back some synagogue for what mine was able to do for me when I was young. Scott, Ross, Tara and Lily, thank you for giving our teens the safe and loving place of experiential learning that every young person needs while growing up. More than anyone else, you guys have been my proxies, and I couldn’t be more grateful.

Thank you to my summer interns: Rabbi Josh Davidson, Rabbi Serena Fujita, Rabbi Craig Axler, Rabbi Judith Siegal, Rabbi Rachel Shafran, Rabbi Rachel Maimin, Rabbi Andy Dubin and Rabbi Andi Feldman Fliegel. Yes, you were a nuisance. You made me work harder during the only time of year we might have slowed down around here. But you were also the only interns who got to be around full-time, who got to go to hospitals with me, and to cemeteries. And you made me feel wonderful for being able to share all of that with you.

Thank you to my year-round interns: Rabbi Fred Greene, Rabbi Leora Kaye, Rabbi Darren Levine, Rabbi Vicki Armour-Hileman, Rabbi Erin Glazer, Rabbi Mara Young, Rabbi Dan Geffen, Rabbi Jason Fenster, Rabbi Deena Gottlieb and Rabbi Zach Plesent. I’m so glad to have shared with you the essence of this amazing synagogue, and to be able to send you out into the world and carry the spirit of Woodlands far and wide.

And to all of you who made it possible through your pledges for me to have these interns, I shall always be especially grateful. It’s been well-known how much I love our intern program, and how much the interns have enriched my time at Woodlands. But we also know how much our congregation enjoys having these young whippersnappers around here, watching them grow, and sending them off to their careers, feeling like we’ve done something really important to get them ready to be rabbis. We have. So please, make sure Rabbi Mara can have her interns too.

A word about Corey Friedlander. He most certainly should have become a rabbi. But instead, he decided to spend his career selling toggle bolts. A strange choice, but lucky us. Because of his not serving the congregations that would have benefitted so enormously from his leadership, this has been our great fortune. And mine as well. Thank you, Corey. We called you Shaliakh K’hilah but, truthfully, I still don’t know what to call you. I’m just glad you’ve been here. Thank you.

And a word about Cantor Jonathan Gordon. For twenty-two years, this man ridiculed and embarrassed me in front of my congregation. In spite of that, because of this man’s humanity and his poetic, principled soul, he never let me forget that I had important work to do. He supported me, guided me, and comforted me. Together, we did a whole lot more than joke around; we reminded us all that we are, first and foremost, human beings. We are flawed, but we are capable of doing great things. Highest among them, sholom … peace. Thank you, my friend.

I need also to thank all of the other rabbis who have served this congregation across the years: Rabbi Dan Isaac, Rabbi Samuel Kehati, Rabbi Stephen Forstein, Rabbi Sandy Ragins, Rabbi Peter Rubinstein, Rabbi Aaron Petuchowski, Rabbi Mark Dov Shapiro and Rabbi Avi Magid. They not only paved the way for me. They helped you to create this amazing little synagogue. They cleared the way for the Woodlands Way, and we are all forever in their debt.

Which brings me to Rabbi Mara Young. People have always given me more credit for being clever than I’ve ever deserved. I’m continually asked if there was some master plan for bringing Mara on as my successor. Yeah, that plan took shape at a Board meeting last August when I announced my retirement and, fifteen minutes later, the Board had offered the position to Mara. Prior to that, we hired her as our intern, then as our sabbatical rabbi, then as our rabbi-educator. Each and every time, we just kept falling in love with her all over again. We watched her learn, watched her do, and watched her be a perfect fit for Woodlands. No master plan. Just a gradually evolving understanding at each step of the way: “She’s right for us.”

For me personally, Mara, I can only say what a delight it has been to work with you these twelve years. To have a rabbinic partner – not just any partner, but one with character, with integrity, with brains, with a kind heart, a creative spirit, and who has enjoyed being here – what a privilege that has been. And to now walk away from this place and know it’s all going to be great, that you and your team are going to carry Woodlands to unimaginable new heights, that’s the best retirement gift of them all.

Okay, I need to end this thing, my last sermon. I think I’ll do so by invoking the words of President Barack Obama. Recently, he’s been recording a podcast called “Renegades” with Bruce Springsteen. In one episode, Springsteen asks when Obama first thought he’d want to run for president.

Obama responded, “If you’re doing it right, running for President is not actually about you. It’s about finding the chorus, finding the collective.”

He talks about visiting a town in South Carolina, to which he’s gone to get the endorsement of a particular state legislator. It’s a long drive, Obama’s down in the polls, it’s pouring rain, and there’s a bad article about him in the New York Times.

So when he walks into whatever center he was appearing at, he’s in a bad mood. But as he’s shaking people’s hands, he hears a woman’s voice chanting, “Fired up? Fired up! Ready to go? Ready to go!”

It turned out to be this wonderful woman named Edith Childs. She had a great smile, a pretty flamboyant dress and hat, and apparently a habit of chanting, “Fired up! Ready to go!”

Obama first thought, “This is crazy.” But everybody was doing it, so he thought, “I better do it too.” And little by little, he started feeling kind of good.

Later, when Obama left that town center, he asked his staff, “Are you fired up? Are you ready to go?” And that’s when he discovered that when you’re doing something hard that you care about, other people will lift you up.

Which is what this congregation has done for me. Again and again, you’ve lifted me up. When the work was exhausting, you reenergized me. When the work was frustrating, you appreciated me. When the work was saddening, you gave me back my smile. And when the work was successful, we reveled in our success together.

If this congregation is great – and it is – it’s because we have done this together. We have loved this place, we have cared for this place, we have kept it strong. And now, you will do the very same with Mara, and with Lance, Abby, Avital and Lara. With Andy, with his Board of Trustees, with all of your committees, and just by showing up, saying hi, and lending a hand. That is always what has made Woodlands. Maybe it’s the Woodlands Way, I don’t know. In the end, it doesn’t matter what the Woodlands Way is, only that each of you knows there must be a special sauce, a special secret, and you keep loving that and you keep treasuring that and you keep sharing it with the next family that walks through these doors.

For all of these moments, and for ten thousand more like them, thank you. I am so blessed to have been here. And that blessing will most assuredly sustain me throughout the journey to come.

At last Friday’s service, Mara blessed me with words that I now use to bless you.

A man was traveling through the desert, hungry, thirsty, and tired, when he came upon a tree bearing luscious fruit and affording plenty of shade, underneath which ran a spring of water. He ate of the fruit, drank of the water, and rested in its shade. When he was about to leave, he turned to the tree and said, “Oh, tree, with what should I bless you? Should I bless you that your fruit be sweet? Your fruit is already sweet. Should I bless you that your shade be plentiful? Your shade is plentiful. That a spring of water should run beneath you? A spring runs strong and true beneath you. But there is one thing with which I can bless you. May it be God’s will that all the trees planted from your seed should be like you.”

Woodlands Community Temple. You have given birth to so many fulfilling spiritual moments in your members’ lives. May it be God’s will that you continue bringing such blessings into our world. God knows, we need them. And may it be God’s will, Woodlands, that all of us who have benefitted from your gifts, may we be your seedlings, and bestow upon others the blessings you have given us. And in that way, your blessings will be your great legacy for countless decades yet to come.

Ken y’hi ratzon.

That’s why we have a night each year to thank our teachers. You — our religious school faculty and adult education faculty — bring us vibrant, passionate, often entertaining presentations that engage us in challenging exercises to help us determine the kind of people we want to be. And with your guidance, we’ll hopefully progress in our abilities to be good, decent, and caring.

That’s why we have a night each year to thank our teachers. You — our religious school faculty and adult education faculty — bring us vibrant, passionate, often entertaining presentations that engage us in challenging exercises to help us determine the kind of people we want to be. And with your guidance, we’ll hopefully progress in our abilities to be good, decent, and caring.