I offered this sermon during Kol Nidre evening 5775 (Oct 3, 2014).

Billy

Fiddler on the Roof is coming back to Broadway this year. That’s good news because everybody should see it at least once. So get tickets for the little ones. There’s a classic scene in which Tevya is explaining how Jewish communities work. He says, “Of course, there was the time when he sold him a horse, but delivered a mule, but that’s all settled now. Now we live in simple peace and harmony and …”

“It was a horse,” interrupts one man. “It was a mule!” proclaims another. Horse! Mule! Horse! Mule!

“Tradition, tradition …”

Fiddler gets more credit for explaining Jewish culture than it probably deserves, but in this case, it gets it right. Judaism has never been monolithic. There’s hardly anything we all agree upon. And we know it!

Argumentation is embedded in Jewish culture. How else could we have a story where two individuals are discussing their synagogue’s minhag, their customary practices – in this case whether to stand up or sit down for the Shema – and one argues that we sit, while the other insists that we stand? So they sought out the oldest member of the synagogue, who explained that the arguing about whether we stand or sit, that is the tradition.

Which makes it surprising and somewhat perplexing that so many of us believe there is only one acceptable way to view the Torah … as God’s revealed word whose literal meaning we must obey … or not. In fact, even among those who believe that the Torah came directly from God, they’ve been arguing about what God meant for thousands of years.

There is, in Judaism, a body of literature called Midrash, a broad genre of Jewish intellectual creativity that began around the 2nd century BCE, perhaps 300 years after the Torah had been written down. Across the centuries, Jews have been questioning the Torah and engaging in some remarkably inventive thinking of their own that doesn’t rewrite the Torah but fills in blanks where parts of the stories seem to have been left out. American Jewish scholar Jacob Neusner teaches that our Jewish sages “did not write about scripture, they wrote with Scripture.” It didn’t bother them one iota that they were playing with sacred text. For them, it was a mitzvah to participate in the continuing creation of Torah. So long as they didn’t contradict what was already there, Torah text was fair game.

Midrash peers in between the words of Torah, and asks what elements of the story are hiding inside. Which brings me to a film that I imagine very few of you have seen: Noah, starring Jennifer Connelly, Emma Watson and Russell Crowe. When Noah came out this past March, you may have thought it belonged to the same category of Bible films as Mel Gibson’s Passion of the Christ. It didn’t, and it doesn’t. Noah disappointed a lot of people who resented how far its film makers had strayed from the original story line. But they hadn’t, because their intention was never to just retell the biblical version. They were creating midrash. The writers, Darren Aronofsky and Ari Handel, are two good Jewish boys. They’re not our “Mel Gibsons,” they weren’t interested in creating a “biblical epic.” They’d studied the Midrash on Noah, and they knew that Jews had a lot of lingering questions about the Flood story, answers which the ancient Midrash has played with, and a few of which they came up with on their own.

I want to share with you some of the midrashim that Aronofsky and Handel used in their film. I want to do this, on Kol Nidre of all times, for two reasons. First, to demonstrate how Jewish thought only begins with the Torah, and that we limit our understanding of Judaism and, quite frankly, of life when we encounter nothing more of Jewish thought than Torah alone. Second, I want to show you the breadth and depth of Jewish learning, to encourage you to do some Jewish learning of your own, to not limit your Jewish knowledge to the stories you were told in childhood. Judaism is more fun than that, and it has so much more to say about life than is apparent in the Torah.

I want to share with you some of the midrashim that Aronofsky and Handel used in their film. I want to do this, on Kol Nidre of all times, for two reasons. First, to demonstrate how Jewish thought only begins with the Torah, and that we limit our understanding of Judaism and, quite frankly, of life when we encounter nothing more of Jewish thought than Torah alone. Second, I want to show you the breadth and depth of Jewish learning, to encourage you to do some Jewish learning of your own, to not limit your Jewish knowledge to the stories you were told in childhood. Judaism is more fun than that, and it has so much more to say about life than is apparent in the Torah.

The story of Noah could be thought of as a simple one, like the one we share with our children, the one we represent by a big boat that has lots of smiling pairs of animals on it, a simple tale in which the wicked are removed from the earth and Creation is given a chance to start anew. But if we look closely at the language of Torah, at the words chosen to tell this story, and give ourselves permission to wonder why those words, why say it that way, we open up new possibilities for how we can understand Noah.

For example, in the very first verse of the Genesis Flood story, Noah is described as a man who was pure and righteous. And that would certainly help to explain how he got chosen to save the world. But the Torah adds an additional word, b’dorotav, which means “in his generation.” Why add that? If he was pure and righteous, isn’t that all that would matter? So we might wonder how b’dorotav changes the verse’s meaning. “Noah was pure and righteous in his generation.” Is that any different? A few questions come to mind? Like would Noah have been considered pure and righteous had he lived in another generation? Perhaps he was a thief, a murderer even, but compared to everybody else in his time – a time when God has decided human beings deserve to die – maybe Noah was still better than the rest. The best of a lot of bad choices. On the other hand, in such a corrupt world, perhaps it was even more difficult to be good than at another time. In a different era, Noah might have been a saint!

In the film, the writers play with this idea. There is no doubt that this Noah cares about the earth, cares about life, cares about his family, would care about others if there were any good people remaining. But this Noah you don’t push around. He’s not the jolly, bearded, Santa Claus-looking fella depicted in the dolls we give to our little ones. This Noah is a warrior. He knows how to wield a sword. And more than a little blood is shed by him in defense of his family and of the Ark. 20th century Torah commentator Nehama Leibowitz writes that while Abraham had been singled out for a mission, “Noah was singled out for survival.” This is not your mother’s idea of “pure and righteous”!

God then instructs Noah to build an Ark. In simple readings of the text, we merely assume he gets the job done, even though, by the Torah’s measurements, it would have been longer than a football field. He had his three sons helping him, but one wonders what technology would have allowed the four of them to complete a project that big, how long would that have taken, and what were Noah’s neighbors doing while this boat was being built next door?

Enter the movie’s construction crew: Semyaza and Ramiel. Giant, transformer-like stone creatures, Aronofsky and Handel did not make them up. The Midrash tells us that Semyaza and Ramiel were celestial beings that had been charged by God with looking after the newly-created human race. According to the Book of Enoch, a collection of stories attributed to Noah’s great-grandfather Enoch and written down maybe 250 years after the Torah, these creatures – known as the Watchers, angels who consorted with humans and fathered the Nephilim who appear in Genesis just prior to the Flood story – the Watchers fell from grace and, as punishment for their behavior, God had them bound for seventy generations. In Noah, the Watchers appear as celestial light encrusted in prisons of stone. They ally with Noah against the evil hordes and assist him in building the Ark.

Now, if you were building an Ark, do you suppose you could keep it a secret for very long? Midrash tells us the Ark’s construction took 120 years, time to grow the lumber, harvest it, and then build the boat. In that time, we are told in a number of Jewish sources across the ages, that people would ask Team Noah what they were doing. When Noah would answer that they were making an Ark to save Creation from the immanent Flood, people would mock him, use vile language, and cause Noah to suffer violently at their hands. So when the movie assigns these giant Watchers to protect Noah, the writers weren’t the first to worry for Noah’s safety.

Then the rain begins. Gentle at first, but probably a wake-up call to the locals who might realize they could have spent the last 120 years building their own boats. They soon organize and attack Noah’s. The Midrash imagines that the lions and other wild animals emerged from the Ark to defend it. In the film, the Watchers protect the Ark. They are all killed while doing so and their celestial lights, formerly trapped in stone prisons, are redeemed by their service to God and to Creation, and rise to heaven where they are welcomed home.

This night of Kol Nidre returns each year to remind us that ours is a heritage in which no one is beyond redemption. Each of us retains the possibility of teshuvah, of returning to goodness and to our essential humanity. The Watchers’ release from their prisons of stone is very much in line with what our heritage has taught throughout the ages. Sci-fi? Definitely! Jewish? That too.

Back to the movie. It’s dark inside the Ark – windows aren’t such a good idea when flood waters are rising. The Genesis text tells us that God instructed Noah to build a tzohar in the Ark. Some translators assume that’s a skylight so that there’s some illumination. But a skylight during a deluge doesn’t seem like such a good idea to me. How ‘bout you? And besides, really bad storms make it pretty dark out anyway. The word tzohar is a hapax legomenon, a word that appears only one time in the entire Tanakh. So not only are we completely unsure as to what the word means, it’s a moment that’s ripe for midrash. Rashi, the most famous and highly-respected commentator of them all (he lived in 11th century France), wrote that some believe the tzohar was a window while others believe it was a wondrous, luminescent stone. Part of the reason for their fanciful thinking here is their agreement that a window would have been a pretty stupid idea. And part of it is that tzohar is similar to tzohorayim, the Hebrew word for afternoon, which may mean the word is less about an object and more about a form of light. In a bunch of midrashic collections, the rabbis imagine tzohar to be a magical stone that contains the very light of Creation, and that’s what the film makers gave to their Noah to brighten his dreary surroundings.

One of the reasons people are unhappy with this film is when Noah decides that God had him build the Ark in order to save the animals but not the humans. Noah believes that he and his family are to tend the Ark’s passengers and will live out their own lives after the Flood but are not themselves to reproduce. The story of human beings is to end with them.

But the message of the Flood story in Genesis seems to be one of second chances. And humankind is included. However, you and I have the benefit of knowing the story. Noah would not have had that advantage. The question is, did the writers violate the simple meaning of the biblical story by building their Noah as an end-of-times fatalist? Let’s take a look.

In the Torah, Noah is told that God is going “to put an end to all flesh.” Hineni mash-khee-tahm et ha’aretz … I will destroy them with the earth. God instructs Noah to take his family into the Ark, but never explicitly says they are to repopulate the earth. This close reading opens up the possibility that Noah thought his job was to build and to captain the Ark, but that he and his family would not survive the trip. The film’s writers asked a great question about Noah’s state of mind. And remember, as long as it doesn’t contradict what’s already written in the Torah, midrash frees us to imagine most anything we want in between the words. By the end of the story, Noah understands that humanity is also to be saved. But at this early point? Well, what would you have thought?

Once the Ark set sail, the animals had to be tended to. The film departs from Midrash here, but both respond to the question, “How could one family have possibly taken care of so many animals for all that time?” Time, by the way, was not forty days and forty nights, but a full year. And that’s actually clear in the biblical text. The rain fell for forty days and nights, but the floodwaters would take many more months to recede and it would be a full year before the Ark’s door would reopen and life on earth could begin again.

While on the Ark, the Midrash tells us that Noah and his family got no sleep because of all the time it took to care for the ship’s passengers. The film depicts Noah’s family, prior to departure, walking the decks waving some sort of herbal smoke machine, and putting the animals to sleep for the duration of the journey. Ancient midrash meets modern midrash. Considering what we know about bears hibernating in the wintertime, the film’s choice may be more believable than what the rabbis imagined. In either case, the question, “How did all those animals get fed?” gets asked by Torah readers because the Torah itself doesn’t say.

One more bit of Midrash for you. The Noah story doesn’t just end with a rainbow and a promise. It has a difficult ending to it, I think because life, even when we get happy endings, can change irrevocably and our happiness is sometimes tempered by the pain, loss, or defeat that someone must experience in order for us to succeed. Why do you suppose that even after the Ark had survived its journey, the animals had emerged and gone out to repopulate nature, and Noah’s family had also begun life anew, why does Noah plant grapes and drink himself into a stupor? Mind you, this wasn’t a one-day boozing; we’re talking a season of planting, harvesting, crushing and fermenting, followed by a formidable period of getting lacquered and hosed. Why?

Two possibilities. First, the movie suggests that Noah believes he failed in his mission. He thought he was to end the human race but was unable to do so. The second possibility appears in the Zohar, Judaism’s preeminent mystical text, which suggests that, upon emerging from the Ark, Noah looked around, saw the devastation which the Flood had caused, and confronted God, demanding to know why mercy could not have ruled the day and saved Creation. God responds with an anthropomorphic slap across the jaw, countering with, “Now you ask me such a question! Perhaps before the Flood, had you confronted Me then, it might have effected a rescue. But you took care only of your family. Too little, too late!” Noah was devastated. That could be why his own ship was three sheets to the wind.

Let me add a personal note. Five years ago, I journeyed on an ark of my own. When I disembarked, my eldest son was gone. Each day since 2009, I have struggled to live my life without my son Jonah in it – my world minus one. As difficult as that has been, I try to imagine what it must have been like for Noah. What of his brothers and sisters? His parents and grandparents? His friends? The millions who would receive no second chance? No wonder he tied one on. How do you live in the aftermath of that kind of indiscriminate, universal destruction?

Our ancestors’ questions for God were never just about the characters in the Torah. They were always trying to better understand what it means for us to be human and how we could best live our lives despite our own shortcomings and the difficulties each of us faces in merely striving to feed and shelter ourselves and those we love. Their questions from a thousand years ago, two thousand years, even three thousand years ago, are our questions too. They may not have known about electricity, plumbing or amazon.com, but they knew about fear and illness and love and peace. Their stories may not have actually happened, but they are as true today as any story you or I will live.

All of these midrashim on Noah’s story demonstrate that Jewish knowledge has never been limited to the text of the Torah. Those Five Books, sacred as they are, merely comprise the starting point for the wealth of experience and wisdom our heritage has waiting for us. Each time we open one of those ancient books, within its pages we will find a mirror reflecting our own concerns, our own questions, our own dreams and hopes, right back at us.

That’s why Jews study. That’s why I believe you will love joining our community of learners here at Woodlands. Whether you study Talmud or Israel with me, a Taste of Judaism or Prayer with Rabbi Mara, the Midrash of Creation with Rav Julius Rabinowitz, or any other adult learning opportunity here at temple, the goal is not to acquire facts but to grow in spirit, not to become encyclopedic but empathetic. My teacher Rabbi Larry Hoffman used to say that we study Jewish texts not just to meet our ancestors but to meet ourselves. It is such a valuable and worthwhile use of time.

Oh, and see the film. It’s a great lesson in Midrash, in the complexity of the human experience which our ancestors have reflected and written about in every year since the Torah got written down.

Avinu Malkeynu … it is Kol Nidre. The time to release ourselves from vows with You that we have not kept. But why shouldn’t we make a few new ones? It’s a New Year, after all. An excellent time to think about how we can strengthen and straighten our highest, noblest values. Learning a bit with You, God, even arguing with You, could be a great new direction in the year ahead. Ken y’hee ratzon … may these words be worthy of coming true.

Closing words at the end of the service

The Torah tells us that Noah entered the Ark “with his sons, his wife, and his sons’ wives.” As is typical for ancient texts, we know little of these women, which means that Midrash is waiting to happen. In this case, midrash from Darren Aronofsky and Ari Handel. Noah’s stepdaughter, Ila, played by Emma Watson, speaks with a Noah who is drunk and in despair at what has become of the planet. The film makers have Ila teaching Noah that God has given us a world in which we are supposed to make choices. There will always be ambiguity and doubt. Nevertheless, we are in possession of mercy and love to assist us in making our choices. With the Ark, God gave humanity a second chance, a chance to live a good life on God’s earth. It is when Noah embraces this second chance and returns to life and to building goodness … that the sun comes out and the rainbow appears.

Avinu Malkeynu … Yours is a world that frequently offers us second chances. On this night of Kol Nidre, of release from vows, may we make a new vow. May we accept Your great gift of teshuvah, of turning, of redemption, of a second chance. And may we ask ourselves, “What will we do with that second chance? What are we doing with that second chance? Are we making certain that we use it for inscribing all of life into the Book of Life?

There’s a very old Jewish story about a woman who’d pretty much had it up to here with her life. It seemed she had nothing but tzuris and couldn’t find a way through the mess. So she went to see her rabbi. The woman spilled out every drop of her woeful tale: her marriage was shaky, her children ungrateful, her job unrewarding, and her health unsatisfactory. The rabbi offered the woman a solution. Walk the width and breadth of our town. Find someone whose life you admire, whose troubles you would exchange for your own, then come back to me and I’ll make the switch. Thanking the rabbi (and oddly, never once thinking this was weird), she headed straight for the home of the wealthiest person in town. His life was perfect. Productive career. Well-behaved children. Good-looking too! But when she looked closely, she saw a house filled with despair: alcoholism, domestic abuse, frightened but resentful children. No way would she trade her troubles for these. As the woman moved from house to house, she discovered that no home was without its challenge, no family free from some tribulation. She returned to the rabbi and thanked him for his offer but, no, she would be keeping her own life and her own difficulties. And with new perspective, she returned home. Did she never fret about the imperfections of her existence? No. But from that day on, she could remind herself that everyone’s life faces challenge. And with that, she lived mostly happily mostly ever after.

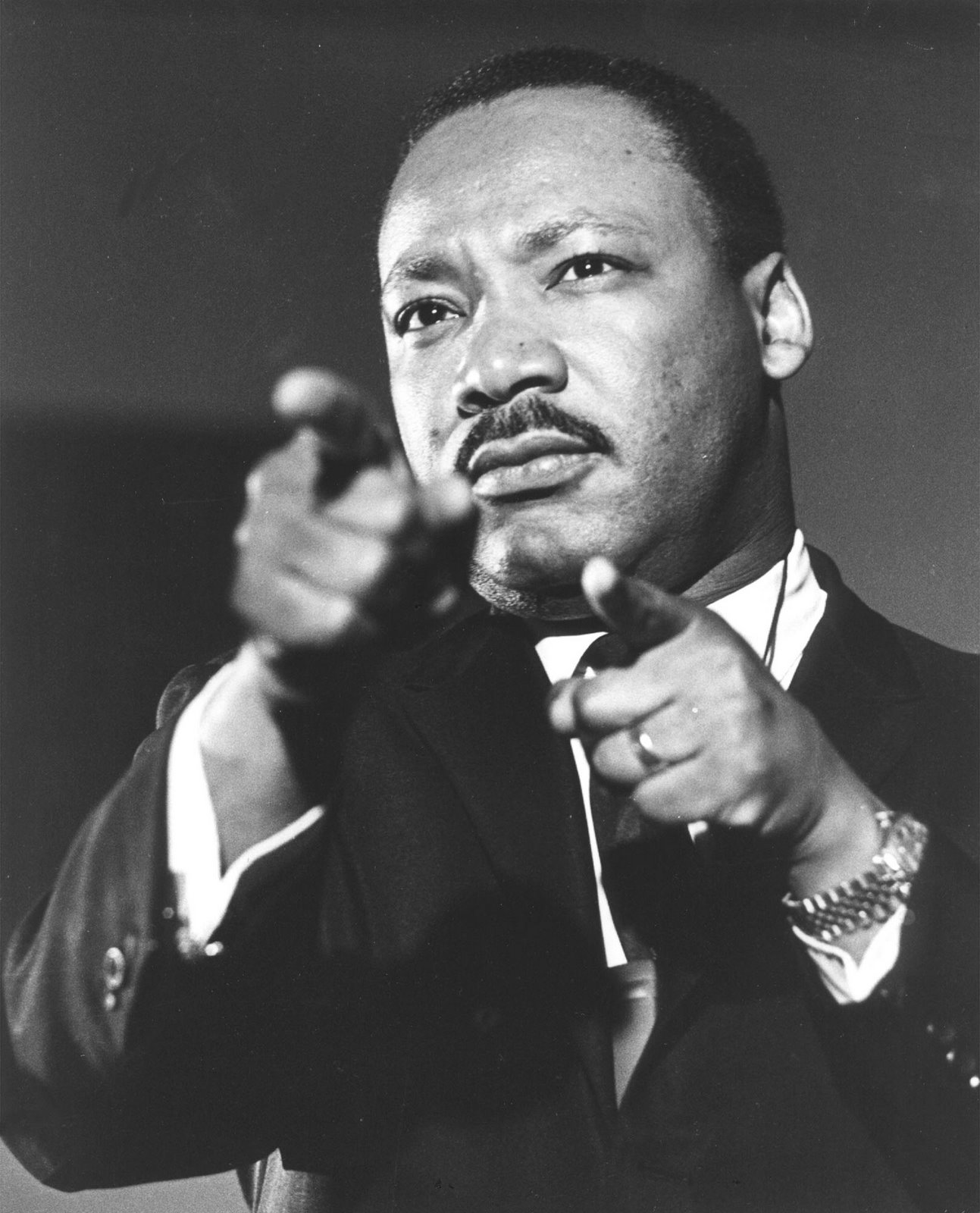

There’s a very old Jewish story about a woman who’d pretty much had it up to here with her life. It seemed she had nothing but tzuris and couldn’t find a way through the mess. So she went to see her rabbi. The woman spilled out every drop of her woeful tale: her marriage was shaky, her children ungrateful, her job unrewarding, and her health unsatisfactory. The rabbi offered the woman a solution. Walk the width and breadth of our town. Find someone whose life you admire, whose troubles you would exchange for your own, then come back to me and I’ll make the switch. Thanking the rabbi (and oddly, never once thinking this was weird), she headed straight for the home of the wealthiest person in town. His life was perfect. Productive career. Well-behaved children. Good-looking too! But when she looked closely, she saw a house filled with despair: alcoholism, domestic abuse, frightened but resentful children. No way would she trade her troubles for these. As the woman moved from house to house, she discovered that no home was without its challenge, no family free from some tribulation. She returned to the rabbi and thanked him for his offer but, no, she would be keeping her own life and her own difficulties. And with new perspective, she returned home. Did she never fret about the imperfections of her existence? No. But from that day on, she could remind herself that everyone’s life faces challenge. And with that, she lived mostly happily mostly ever after. So on this weekend that honors the life and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr,, it’s not hard to equate Dr. King with the great biblical prophets. Only moments ago, we heard his immortal words in Washington, “I have a dream that one day … the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood. […] I have a dream that one day … little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.”

So on this weekend that honors the life and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr,, it’s not hard to equate Dr. King with the great biblical prophets. Only moments ago, we heard his immortal words in Washington, “I have a dream that one day … the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood. […] I have a dream that one day … little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.” A learned rabbi once asked his students how they could tell when the night had ended and day had begun. “Could it be,” said one student, “when you can see an animal in the distance and tell if it is a sheep or a dog?” “No,” answered the rabbi. Another asked, “Is it when you can look at a distant tree and tell if it is a fig tree or a peach tree? “No,” answered the rabbi. “The night has ended and day has begun … when you can look upon the face of any man or woman, and see that it is your brother or sister. Because if you cannot see this, it is still night.”

A learned rabbi once asked his students how they could tell when the night had ended and day had begun. “Could it be,” said one student, “when you can see an animal in the distance and tell if it is a sheep or a dog?” “No,” answered the rabbi. Another asked, “Is it when you can look at a distant tree and tell if it is a fig tree or a peach tree? “No,” answered the rabbi. “The night has ended and day has begun … when you can look upon the face of any man or woman, and see that it is your brother or sister. Because if you cannot see this, it is still night.”

As far as this last question, the Torah tells us they didn’t. For the duration of their trip – all forty years of it – neither their clothes nor their shoes ever wore out. They must have had dramatically different manufacturing standards back then because I sure can’t get a shirt to stay free of pilling to save my life.

As far as this last question, the Torah tells us they didn’t. For the duration of their trip – all forty years of it – neither their clothes nor their shoes ever wore out. They must have had dramatically different manufacturing standards back then because I sure can’t get a shirt to stay free of pilling to save my life.