Shed a Lotta Light!

There’s a very old Jewish story about a woman who’d pretty much had it up to here with her life. It seemed she had nothing but tzuris and couldn’t find a way through the mess. So she went to see her rabbi. The woman spilled out every drop of her woeful tale: her marriage was shaky, her children ungrateful, her job unrewarding, and her health unsatisfactory. The rabbi offered the woman a solution. Walk the width and breadth of our town. Find someone whose life you admire, whose troubles you would exchange for your own, then come back to me and I’ll make the switch. Thanking the rabbi (and oddly, never once thinking this was weird), she headed straight for the home of the wealthiest person in town. His life was perfect. Productive career. Well-behaved children. Good-looking too! But when she looked closely, she saw a house filled with despair: alcoholism, domestic abuse, frightened but resentful children. No way would she trade her troubles for these. As the woman moved from house to house, she discovered that no home was without its challenge, no family free from some tribulation. She returned to the rabbi and thanked him for his offer but, no, she would be keeping her own life and her own difficulties. And with new perspective, she returned home. Did she never fret about the imperfections of her existence? No. But from that day on, she could remind herself that everyone’s life faces challenge. And with that, she lived mostly happily mostly ever after.

There’s a very old Jewish story about a woman who’d pretty much had it up to here with her life. It seemed she had nothing but tzuris and couldn’t find a way through the mess. So she went to see her rabbi. The woman spilled out every drop of her woeful tale: her marriage was shaky, her children ungrateful, her job unrewarding, and her health unsatisfactory. The rabbi offered the woman a solution. Walk the width and breadth of our town. Find someone whose life you admire, whose troubles you would exchange for your own, then come back to me and I’ll make the switch. Thanking the rabbi (and oddly, never once thinking this was weird), she headed straight for the home of the wealthiest person in town. His life was perfect. Productive career. Well-behaved children. Good-looking too! But when she looked closely, she saw a house filled with despair: alcoholism, domestic abuse, frightened but resentful children. No way would she trade her troubles for these. As the woman moved from house to house, she discovered that no home was without its challenge, no family free from some tribulation. She returned to the rabbi and thanked him for his offer but, no, she would be keeping her own life and her own difficulties. And with new perspective, she returned home. Did she never fret about the imperfections of her existence? No. But from that day on, she could remind herself that everyone’s life faces challenge. And with that, she lived mostly happily mostly ever after.

You know what I don’t like about this story? Even though the woman learned an important lesson about success and happiness, her experiences left her unmoved and unresponsive to the others whom she’d encountered. Frankly, this Jewish story doesn’t seem very Jewish to me. After all, are we not the people whom God instructed, “You shall love your neighbor as yourself” rather than “You shall feel better than your neighbor about yourself”? And Hillel not the famed rabbi who insisted that while we must indeed care for ourselves (“If I am not for myself, who will be for me?”), did he not immediately follow that teaching with, “But if I am only for myself, what am I?”

Ours is a tradition of empathy (of feeling the pain of others) and of action (of taking needed steps to help alleviate another’s pain). Which is why our biblical prophets are so dear to us. When Isaiah calls us to feed the hungry, Jeremiah to plead the case of the poor and needy, and Amos to let justice roll down like waters, these are the teachings that have shaped the generations of our people, the Jewish directives that have guided us down the paths which we walk.

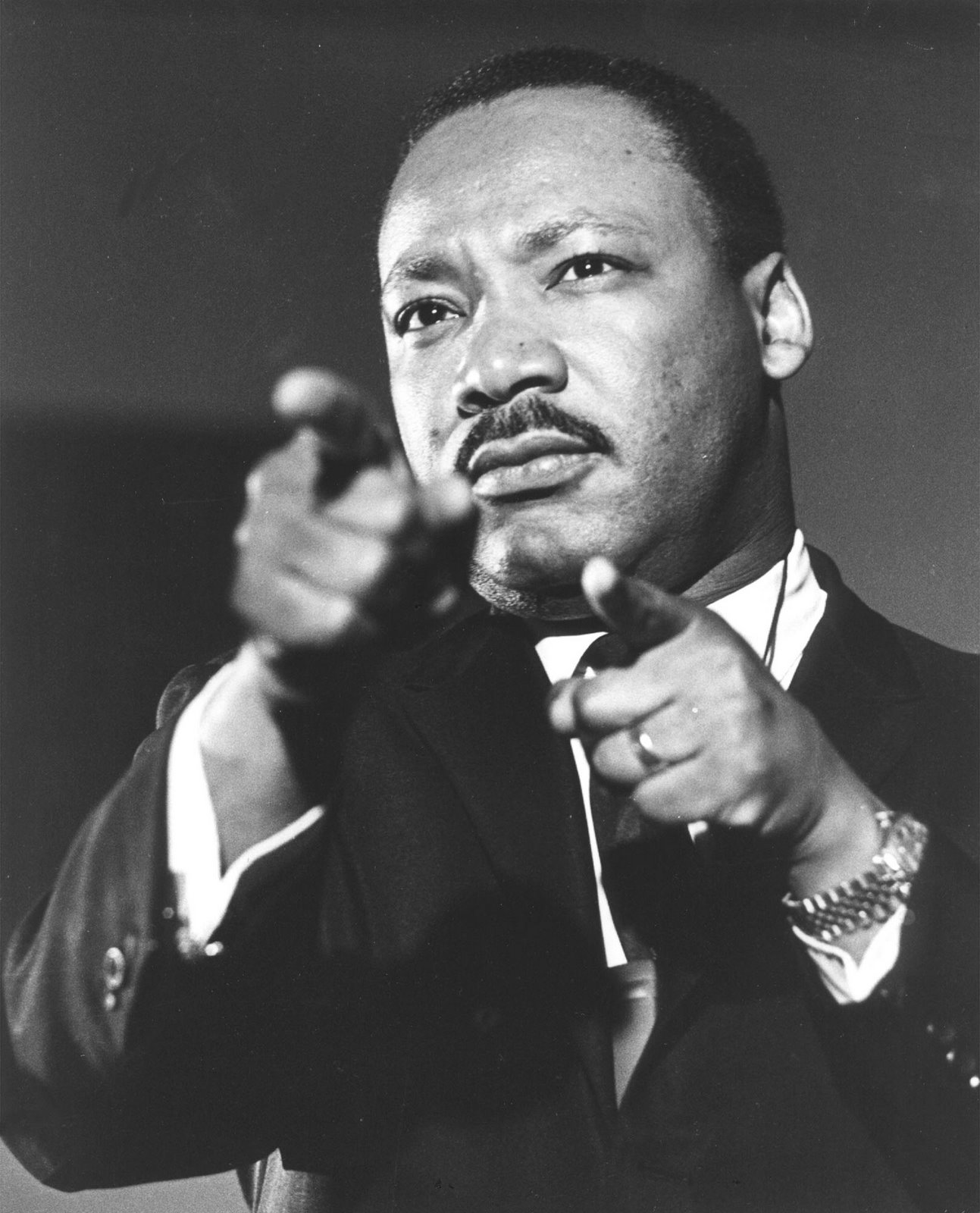

So on this weekend that honors the life and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr,, it’s not hard to equate Dr. King with the great biblical prophets. Only moments ago, we heard his immortal words in Washington, “I have a dream that one day … the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood. […] I have a dream that one day … little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.”

So on this weekend that honors the life and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr,, it’s not hard to equate Dr. King with the great biblical prophets. Only moments ago, we heard his immortal words in Washington, “I have a dream that one day … the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood. […] I have a dream that one day … little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.”

Dr. King’s message always was that we should step forward to advocate for each other. Not just for ourselves. And not just for those who look like us. That’s why “Black Lives Matter.” It’s not that all lives don’t matter; they do. But African-Americans are being brutalized and killed by some who have been charged with protecting us. Now is the time for us to stand with them. We must all stand together. That’s what our Jewish tradition has taught us. That’s what good people do. That’s what a mensch does.

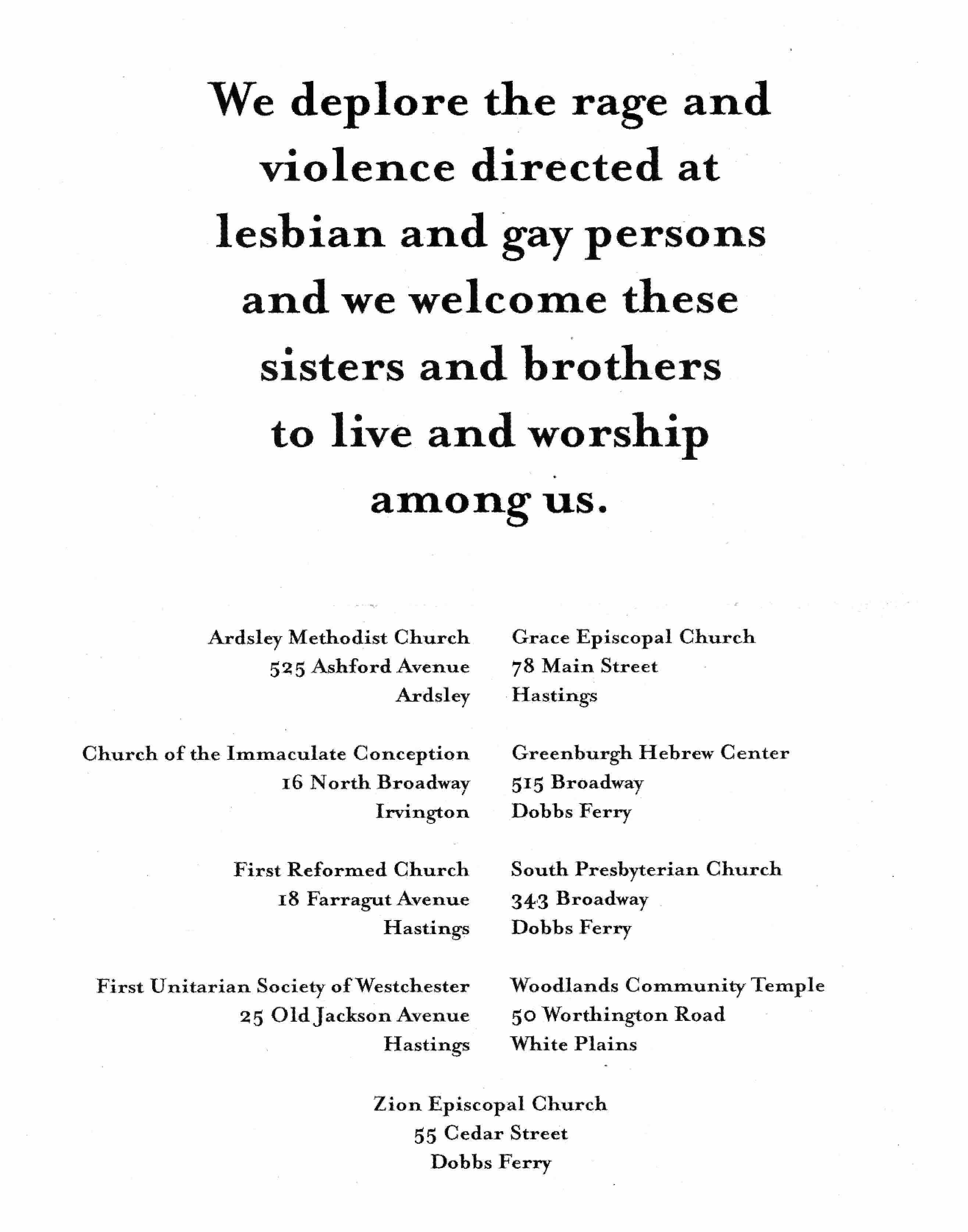

A couple of weeks ago, there was an antisemitic incident in our area. Six swastikas and the word “Jews” were spray-painted on a home that was also pelted with eggs. The Jewish community spoke out, as it should. I was talking with Rabbi Mara Young about this and we both expressed appreciation, and gratitude, that we live in a time where injustice is something we can all face head-on, together. We need no longer remain quiet, hoping that bigotry will just go away, knowing that it won’t. Today, we can speak out. We don’t always do so, but we can. Jews and non-Jews standing side-by-side, neighbor with neighbor, to condemn this hurtful behavior. This time, it’s “Jewish Lives Matter.”

Is this not the very lesson that Dr. King wanted us to learn? To embrace difference, to celebrate it, and to protect it. To build a world where all lives truly matter. And to get there by proclaiming as loudly as we can, from the highest mountains, that black lives matter, Jewish lives matter, Syrian lives matter, immigrant lives matter, Muslim lives matter.

I want to share with you a beautiful video that was released earlier this week. You’ve probably heard of The Maccabeats. They’ve been making all those great a cappella Hanukkah videos of the past few years. Natural 7 is a black a cappella group that joined with The Maccabeats to record a James Taylor tune entitled “Shed a Little Light.” It’s a Martin Luther King Day message. It’s a Jewish message. It’s a human message for us all.

Give it a listen, then come back and read the end of this piece …

“We are bound together in our desire to see the world become a place in which our children can grow free and strong.” That’s Dr. King’s message. That’s the message our ancestors received when they stood at Mount Sinai. That’s the message our prophets tried to remind later generations when they faltered in their commitment to the well-being of all and spent too much time and energy looking only after themselves.

A learned rabbi once asked his students how they could tell when the night had ended and day had begun. “Could it be,” said one student, “when you can see an animal in the distance and tell if it is a sheep or a dog?” “No,” answered the rabbi. Another asked, “Is it when you can look at a distant tree and tell if it is a fig tree or a peach tree? “No,” answered the rabbi. “The night has ended and day has begun … when you can look upon the face of any man or woman, and see that it is your brother or sister. Because if you cannot see this, it is still night.”

A learned rabbi once asked his students how they could tell when the night had ended and day had begun. “Could it be,” said one student, “when you can see an animal in the distance and tell if it is a sheep or a dog?” “No,” answered the rabbi. Another asked, “Is it when you can look at a distant tree and tell if it is a fig tree or a peach tree? “No,” answered the rabbi. “The night has ended and day has begun … when you can look upon the face of any man or woman, and see that it is your brother or sister. Because if you cannot see this, it is still night.”

Eloheinu v’elohei avoteinu v’imoteinu, dear God, God of our ancestors, God of all humankind, we are forever grateful that You gave to us these precious and sacred gifts of empathy, kindness and compassion. Understanding that none are immune from life’s troubles, may we use these gifts to bring great good into our world. May we not stand by idly when another bleeds. May we rise and be counted when our community needs us. May we rise and be counted when someone else’s community needs us. May we appreciate not only what we have, but what others lack. And may we look upon the face of every man and woman and see that he is our brother, she our sister.

Let the ties between us shed a little light on everybody. Bound together by the task that stands before us, let us travel that road together, and welcome a new day for all.

Ken yehi ratzon … may these words be worthy of coming true.