On Lech Lecha (Genesis 12:1-17:27)

“Abram went forth as God had commanded him, and Lot went with him. Abram was seventy-five years old when he left Haran.” (Genesis 12:4)

Careful there. Reading that first sentence, you might think this is a duplicate of the other D’var Torah I wrote this week (“When I Become Old”).

You wouldn’t be entirely incorrect.

This past August, I stopped by ye olde stomping grounds at Woodlands Community Temple to attend a Shabbat Evening Service. Having retired, I’m no longer on the bimah but I do drop by every now and then. On this particular evening, WCT welcomed Cantor David Frommer who sang (cantors do that!) and he spoke (I love when cantors do that!). It might interest you to know that David has a couple of other titles he uses on occasion. At his place of employment, David is addressed as Chaplain Frommer. On his stationary, it reads, “Maj. David Frommer.” If you want a cool title like that, first become a rabbi or a cantor, then get yourself a commission at the United States Military Academy in West Point, New York.

Chaplain Frommer spoke that evening about the privilege of serving his country and how more members of the Jewish community should do so. I wasn’t exactly David’s target audience, but I was really inspired by his words.

Despite the many failures and disappointments in American governance that we hear about each day, I’m deeply proud and grateful to live in the United States. I never served in the military (the Vietnam War-era draft having ended just prior to my 18th birthday) but I did spend a summer in the USO. Our small company performed for American and NATO troops, presenting to hundreds of soldiers on major bases throughout Germany and Italy, and to a dozen or so soldiers at a time who were serving in tiny command posts located in the farthest reaches of the European theater. I felt extremely fortunate to be able say “Thank you for your service” in such an exciting and rewarding manner.

After that evening’s Shabbat service, I sought out Chaplain Frommer and told him how much I enjoyed his presentation and, were I younger, that I might very well have taken him up on his request to enlist. But now counting myself among the long, greying line of the aged (as opposed to “the long grey line” of West Point cadets), the best I could do is offer to help out if he felt there was something I could do for him.

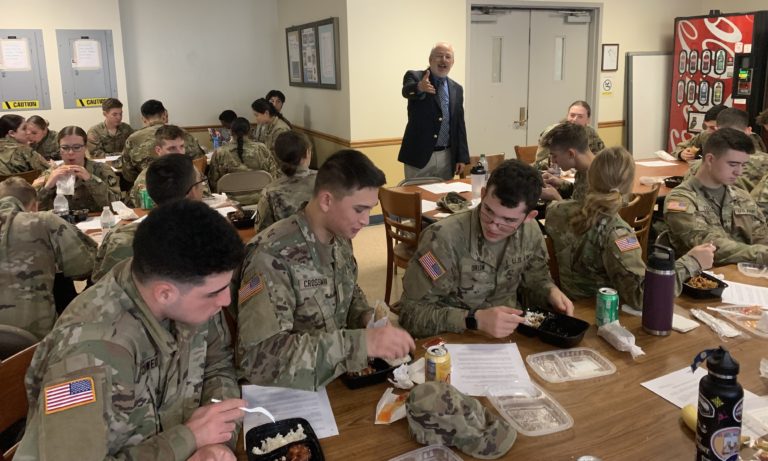

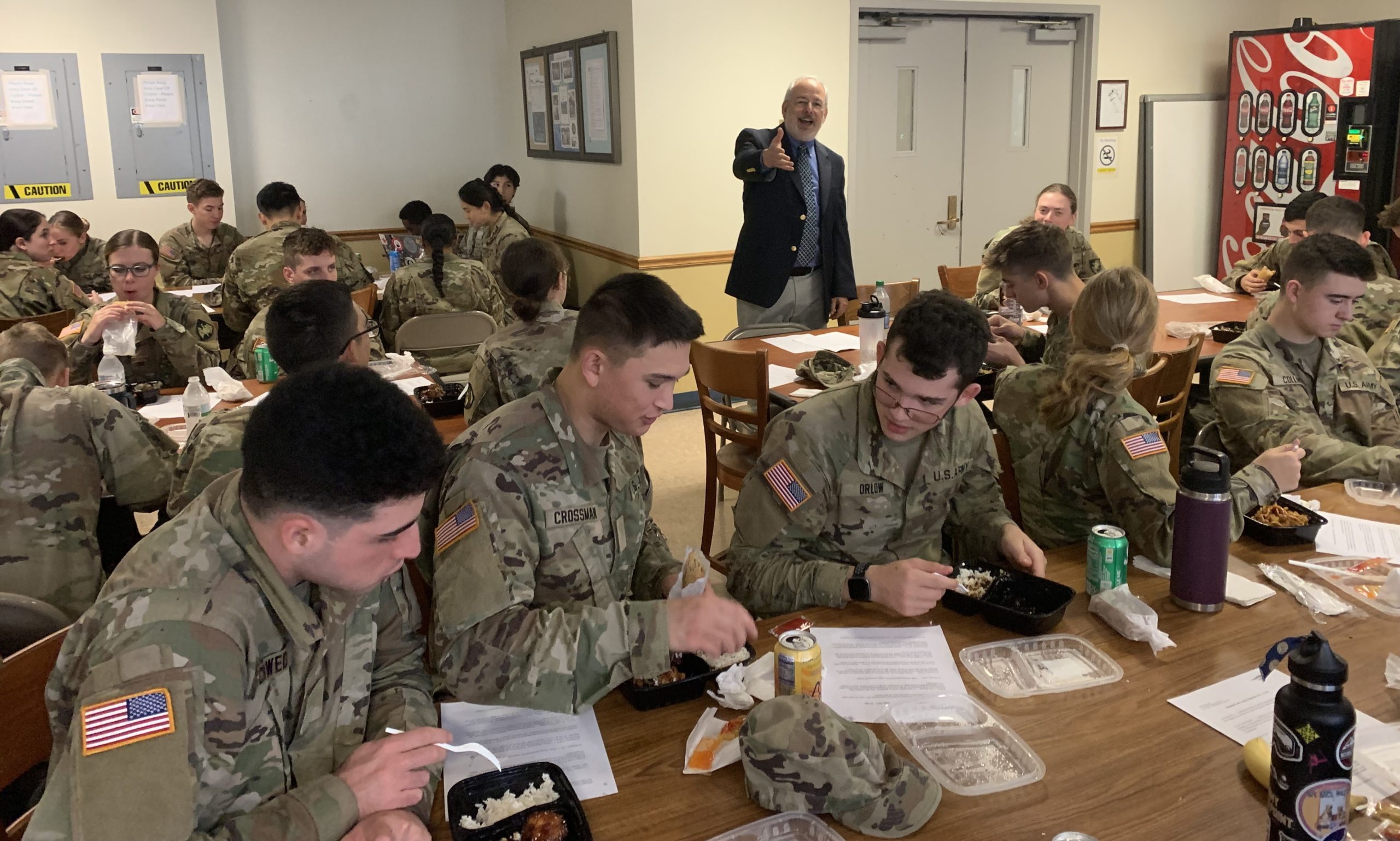

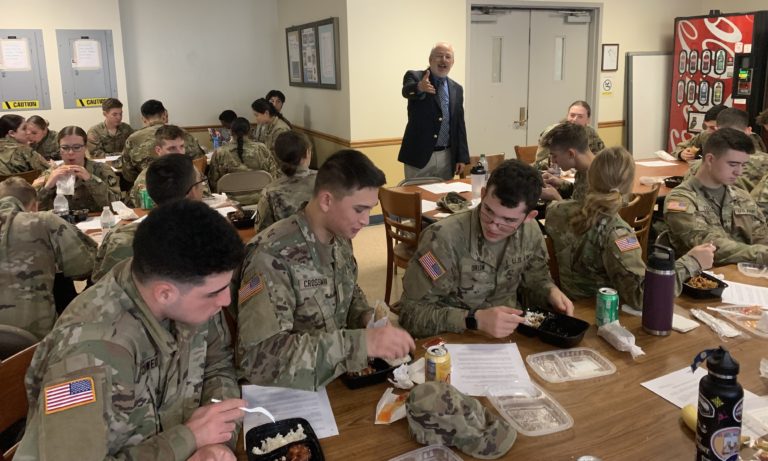

And that’s how I found myself at West Point for lunch this week.

And that’s how I found myself at West Point for lunch this week.

Sixty or so college-age cadets were seated cafeteria-style in the large dining space, buoyantly chatting with each other as they heartily consumed kosher Chinese food from Monsey. It was during their meal that I was introduced and given 25 minutes or so to share some Torah.

While you teachers out there might shudder at the thought of trying to speak to a roomful of young, hungry students while they sat with friends during one of the few breaks in their day, these kids were as polite and attentive as one could ever imagine. And I loved the gone-too-quickly 25 minutes I was able to spend with them.

I began by telling them about my other D’var Torah that I wrote this week for the World Union for Progressive Judaism, a piece about getting older and, like Abraham (who the Torah says lived for 175 years), making sure those later years are filled with new experiences built atop a foundation of ever-increasing wisdom.

But, I continued, that’s probably not the most relevant topic for a group of 18-22 year olds. As I began to look for something else in Lech Lecha that I could share with them, it occurred to me that, with a bit of adjustment, these texts, and almost this same point, could work.

My thesis for the cadets was simple: Over time, regardless of age, many of us grow old in a metaphorical manner. We might be stung by disappointment. We might lose our youthful idealism. We might calcify, petrify, and otherwise toughen up into old and hardened ways. We might not become hard-of-hearing, but unhearing. We might not become blind, but unseeing. We might not die, but our feelings might.

I quoted General Colin Powell (not someone who frequently figured in sermons when I was un-retired). “Leadership is solving problems. The day soldiers stop bringing you their problems is the day you have stopped leading them. They have either lost confidence that you can help or concluded you do not care. Either case is a failure of leadership.”

I told the cadets that I love this text, because it emphasizes the humanity of the military leader and of the military soldier. Both need to retain their most human emotions and feelings, and respect the same in others.

The young people at West Point are enrolled in program that grooms them to become leaders, militarily for a while and then perhaps something else when their period of service is complete. While they train, it’s crucial that they think about what it means to be a leader. Giving troops the orders that may determine whether young men and women live or die, this is certainly part of the military leader’s job description. But remaining approachable — especially by those whose lives might one day be placed in the line of danger — preserving and nurturing those parts of themselves that will allow a solder to bring them their problems, that is extraordinary leadership.

The young people at West Point are enrolled in program that grooms them to become leaders, militarily for a while and then perhaps something else when their period of service is complete. While they train, it’s crucial that they think about what it means to be a leader. Giving troops the orders that may determine whether young men and women live or die, this is certainly part of the military leader’s job description. But remaining approachable — especially by those whose lives might one day be placed in the line of danger — preserving and nurturing those parts of themselves that will allow a solder to bring them their problems, that is extraordinary leadership.

I served as a congregational rabbi for 34 years, 28 of those years with the same congregation. Throughout that time, I observed in myself, and in other rabbis too, an evolution; namely, that through the repetition of tasks we have mastered, our attitudes can and probably will change. I have hurried people along who shouldn’t have been hurried, not because I was in a hurry (although sometimes I was) but because, owing to my mastery of the tasks at hand, I was able to move more and more quickly. What’s curious here (and what I should have learned far earlier) is that, in my line of work, not only do laypeople not move as quickly as their clergy, ofttimes they don’t want to. The work we do (in my case, as a rabbi officiating at B’nai Mitzvah, weddings, funerals and so much more) includes moments when the everyday rush slows down because these are moments that are too special to rush.

But there I was, this young rabbi who, at times, grew impatient and frustrated when it took more time to bring someone to a place of understanding or completion. I lashed out (perhaps unknowingly, perhaps not) when I felt my time was more important than their experience. And I saw others do this too — other rabbis, as well as doctors, teachers, police officers, salespeople and more.

Life, I told the cadets, isn’t so much about slowing down as about paying attention, taking the time to pay attention. For them, maybe not in the heat of battle, but when they could make the time, take the time, and that it might make a difference. Human lives aren’t only at stake on the battlefield; every moment of contact with another person is a moment during which that person can be ordered, or they can be honored. Admittedly, both can happen at the same time but I hope they understood what I meant.

In Genesis 12:9 we read, “Then Abram journeyed by stages toward the Negev.” I learned from Onkelos (in preparing my other D’var Torah) that Negev is related to Hebrew verb that means “dry.” The desert is dry. The land after the Flood became dry. And if we’re not careful, we too can “dry.” We can lose our youthful exuberance, our ideals, our sense of sympathy and, yep, our patience. We have so much to offer each other but, in the rush to success, we can lose sight of the purpose of our journey. We pursue grand ambitions (and we should) but because we have “dried,” because we have hardened, we have less and less to offer the people around us.

The I quoted General Douglas MacArthur. “A true leader has the confidence to stand alone, the courage to make tough decisions, and the compassion to listen to the needs of others. He does not set out to be a leader, but becomes one by the equality of his actions and the integrity of his intent.”

There is wisdom that comes with advancement. To these cadets I suggested it was the wisdom of resolving conflict with words rather than with weapons, and what a truly magnificent achievement that is. Soldiers or not, we all face moments of choice between words and weapons, when we can work to resolve differences and disagreements through mutual respect for common hopes and dreams, or we can strive to impose our desired outcome without the hard work of negotiation and compromise.

When I think about the number of heads I butted in my youth, and how much more adept I became, as the years marched on, at working with people to find shared resolutions, I’m so glad I moved in the direction of growing attentiveness and compassion, rather than of well-honed skills alone.

In Genesis 14:14-15, seventy-five year old Abram “heard that his kinsman’s [household] had been taken captive. He mustered his retainers, born into his household, numbering three hundred and eighteen, and went in pursuit as far as Dan. At night, he and his servants deployed against them and defeated them.”

At a time when that baton would have already been passed and such tasks would belong to a new generation, Abram took note. The new generation was being held captive somewhere and it was up to an old man to save the day.

This is where time and experience pay off, when we understand difference between biding our time and knowing it’s time to act decisively. Whether we are truly old (speak for yourself!) or we are well-seasoned, the key for all of us is to remain inspired and determined, to maintain our principles and integrity from day one (as cadets or rabbis or wherever are skills lie) to day last (as perhaps 5-star generals, CEOs, veteran educators, etc).

Then, as I wrapped things up, I quoted a general one last time. This time, General Dwight D. Eisenhower. “The supreme quality of leadership is integrity.”

Time will pass. Perhaps enough time to gray our hair and go on Medicare. Or enough that people have begun to look up to us as the voice of experience and (we should be so lucky) of reason. The trick is to not allow time to pass us by, to do what’s needed to remain strong of principle, of ideals, of conviction, of action. And we need to do so until the day we finish our own service – service to country, to ourselves and those we love, and our service to God.

Shabbat shalom.

Billy

P.S. Many, many thanks to Chaplain David Frommer for inviting me up to West Point. It’s hard to say whether this or my time in the USO was more fun!

And that’s how I found myself at West Point for lunch this week.

And that’s how I found myself at West Point for lunch this week. The young people at West Point are enrolled in program that grooms them to become leaders, militarily for a while and then perhaps something else when their period of service is complete. While they train, it’s crucial that they think about what it means to be a leader. Giving troops the orders that may determine whether young men and women live or die, this is certainly part of the military leader’s job description. But remaining approachable — especially by those whose lives might one day be placed in the line of danger — preserving and nurturing those parts of themselves that will allow a solder to bring them their problems, that is extraordinary leadership.

The young people at West Point are enrolled in program that grooms them to become leaders, militarily for a while and then perhaps something else when their period of service is complete. While they train, it’s crucial that they think about what it means to be a leader. Giving troops the orders that may determine whether young men and women live or die, this is certainly part of the military leader’s job description. But remaining approachable — especially by those whose lives might one day be placed in the line of danger — preserving and nurturing those parts of themselves that will allow a solder to bring them their problems, that is extraordinary leadership.